|

Even though the Republican tax and spend bill that cleared the United States House of Representatives last month no longer authorizes the sale of thousands acres of public land, state lawmakers in New Mexico say they will continue to monitor how the federal government’s actions toward public lands could impact Native nations.

As the interim legislative Indian Affairs Committee on Monday planned its work for the rest of 2025 at its first meeting since this year’s legislative session, two members said the U.S. government’s plan to sell public lands could threaten tribal sovereignty and economic development in New Mexico, which is home to 23 Indigenous nations. Rep. Patricia Roybal Caballero, an enrolled member of the Piro Manso Tiwa Tribe and an Albuquerque Democrat, said she anticipates the federal government’s sales of public lands may affect tribal sovereignty, and she wants to know what legal mechanisms are available to the state government to “push back against those land grabs.” “I envision us going back to the days of land grabs,” Roybal Caballero said. U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez (D-N.M.), who co-founded the Bipartisan Public Lands Caucus earlier this year, last month applauded the removal of a provision in the budget bill that would have authorized the sale of thousands acres of public land in Utah and Nevada. At the time, Mark Allison, executive director of conservation advocacy group New Mexico Wild, said this is the first of many fights in coming days to stave off efforts to privatize public lands. “The same forces that tried to sneak this land grab through would love nothing more than to come after New Mexico’s public lands next time,” he said. Rep. Charlotte Little, an Albuquerque Democrat from San Felipe Pueblo, said on Monday she wants the committee to receive a report on the impact of the federal government’s proposed actions toward the Chaco Canyon and Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks national monuments, and how those actions could also affect economic development in the surrounding areas. New Mexico’s federal delegation, led by U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), in April asked the federal government to leave intact Tent Rocks along with Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument and Rio Grande del Norte, which they said were “under consideration for reduction or elimination.” Roybal Caballero also said she wants the committee to discuss issues related to sustainable management of tribal lands including water rights, resource extraction and environmental protection. By the end of the year, the committee is expected to endorse legislation for the 2026 legislative session.

0 Comments

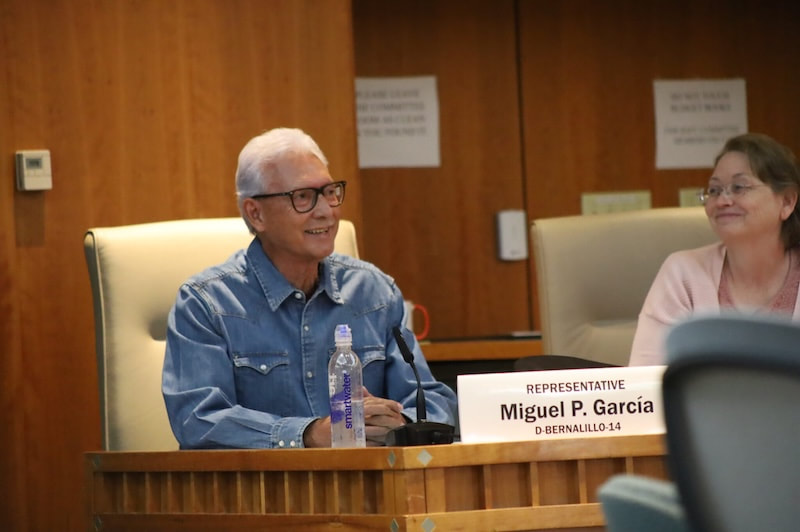

Rep. Miguel Garcia (D-Albuquerque) wants U.S. Attorney for the District of New Mexico Ryan Ellison to attend an interim legislative Land Grant Committee meeting this year. Garcia is showing speaking during the committee’s first meeting since the most recent legislative session on May 30, 2025. (Photo by Austin Fisher / Source NM) A state lawmaker is asking the top federal prosecutor in New Mexico to reopen a case that allowed the American government to take millions of acres of commonly owned land promised to New Mexicans in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Rep. Miguel Garcia (D-Albuquerque) on May 28 sent a letter to U.S. Attorney for the District of New Mexico Ryan Ellison asking him to reopen a 128-year-old court case called United States v. Sandoval. Garcia is asking Ellison to attend one of this year’s interim legislative Land Grant Committee hearings, at which land grant attorney Narciso Garcia will present the legal arguments and questions surrounding the case to either Ellison or his designee, and the committee will ask him to intervene. Last Friday, at the committee’s first meeting since this year’s legislative session, Garcia said he took it upon himself to make the request, and that Ellison’s office is deliberating how to respond to it. Ellison’s office declined to comment. The case deals with commonly owned land — locally managed lands meant to sustain communities — in seven areas in New Mexico granted by the Spanish Empire and later recognized by Mexican law. The justices ruled that the common lands were actually owned by the Spanish Empire, and therefore became the U.S. government’s property as a result of the the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at the end of the Mexican-American War. During this period, land speculators, including U.S. government officials, took advantage of adverse U.S. Supreme Court decisions to defraud communities of their common lands, Arturo Archuleta, director of the New Mexico Land Grant Council and the University of New Mexico Land Grant-Merced Institute, told the committee. The Sandoval decision resulted in the seven land grants shrinking from an average of 450,000 acres to 1,500 acres, Garcia wrote.

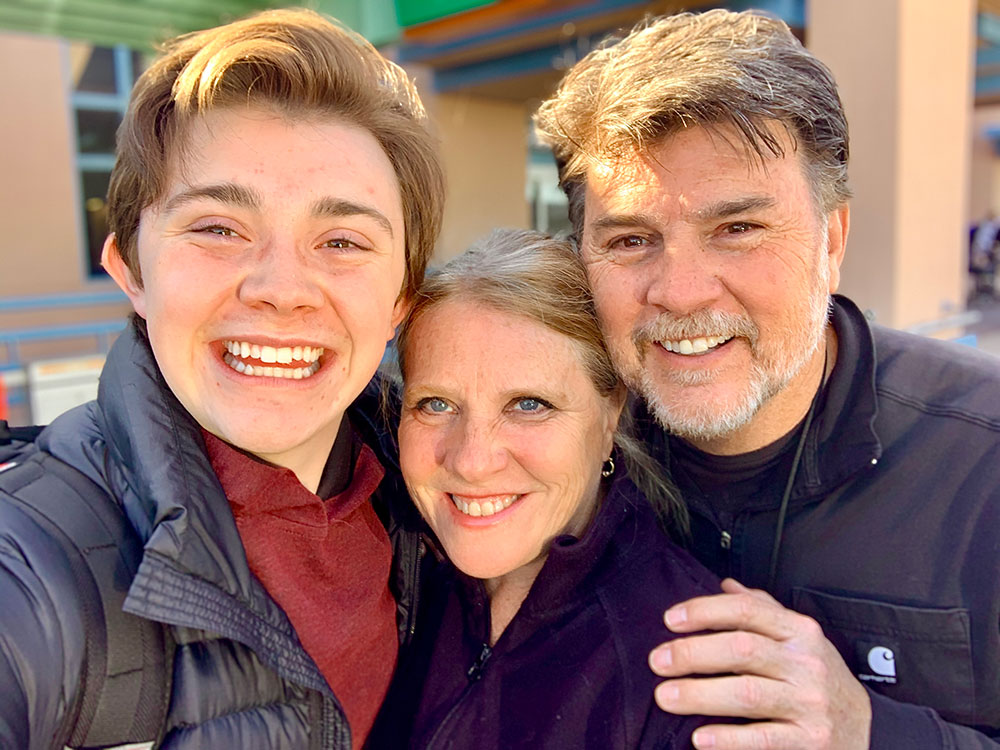

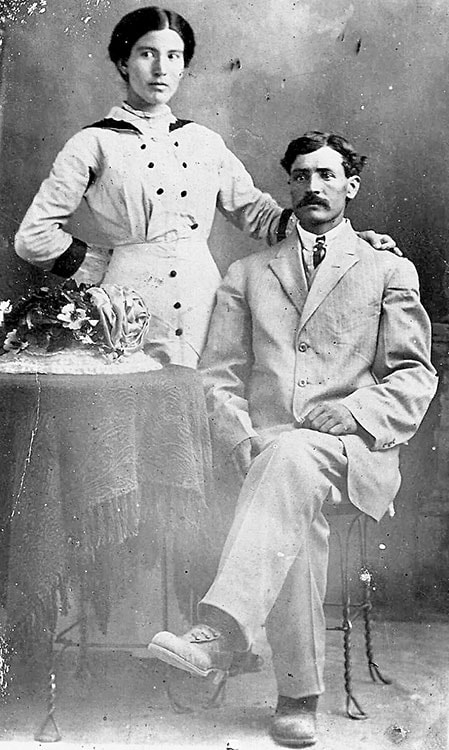

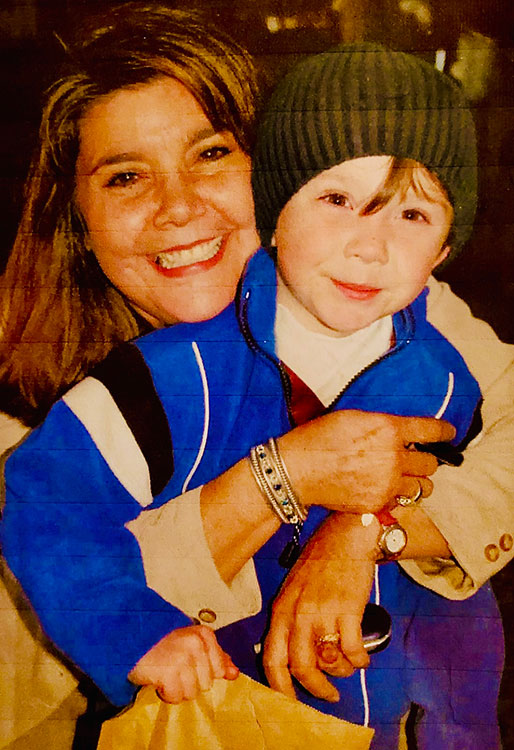

He wrote that the ruling was a travesty of justice, and told the committee that it resulted in the depopulation of some land grant communities who could no longer herd as many cattle and sheep or produce as many forestry products. “This was devastating for these communities because this is what brought on poverty in our state,” Garcia told the committee. “This is a good example of how our land grant communities were turned from a vibrant, self-sustaining community to an impoverished community.” Garcia attached to the letter a 2018 working paper written by John Mitchell, who argues that after Mexico ceded the Territory of New Mexico to the U.S., Congress failed to incorporate it and allowed a temporary government to grant common lands to the inhabitants, which took away jurisdiction from the U.S. Supreme Court concerning land titles in the territory. “Ultimately, the decision still belongs to the New Mexico Supreme Court who could hold that the de facto government did in fact grant common lands under existing law,” Mitchell wrote. Interview with Maximiño Manzanares By Jessica Rath When I interviewed MariaElena Jaramillo in February, she told me about the Matachines Dances being revived in El Pueblo de Abiquiú, and later suggested that I get in touch with Maximiño Manzanares if I wanted to learn more. Several other people in Abiquiú mentioned the name – in connection with teaching music and art at the elementary school, for example, or: “what a kind, community-oriented person this is”, I heard. The perfect subject for an interview, I thought, and when Maximiño was kind enough to set aside some time for a conversation, we met at the Abiquiú Inn to talk. They’re the youngest person I’ve interviewed so far – they’re 24 years old. Maximiño uses the pronouns “they” and “them”, and because I strongly believe that everybody has the right to decide this, I will honor their wishes, of course. Maximiño was born and raised in Santa Fe, which is called O’ga P’ogeh Owingeh (White Shell Water Place) in the Tewa language, as I learned. Maximiño comes from an intergenerational line of musicians, including their Dad David Manzanares, their Tío Michael Manzanares, their late Grandpa Herman Manzanares, as well as many more aunts, uncles, cousins, and other relatives.Music, singing, dance, and other artistic endeavors are embedded in their family’s genes and go back many generations. It was a delight to hear stories not only about Maximiño’s childhood, but also about their Tías, Tíos, Abuelos, and Bisabuelos [for our Spanish-challenged readers: Aunts, Uncles, Grandparents, and Great-Grandparents]. “Both my Mom and my Dad have amazing musical backgrounds, and they have immersed me in music my whole life,” Maximiño told me. “On the day I was born, my parents and I were joined by my Tío Michael, my cousin Peter, and all four of my grandparents. My Grandpa Herman brought his guitar, and all of my family who was there sang Las Mañanitas, one of our traditional birthday songs, for me. In my first moments of being earthside, my family sang to me to welcome me to the world. Part of the lyrics translate to: “On the day that you were born, all the flowers bloomed.” Las Mañanitas means “the early mornings”, and it's a song that we sing to honor people on their birthday. So, it was, is, and always will be a deep blessing for me that, on the day that I was born, my family came together to sing me into the world.” What an absolutely delightful story, listening to the music your family performs for you the moment you are born! What a wonderful welcome. But there is more. Maximiño continued: “When my Momma was pregnant with me, she and my Dad would play music all the time, even with headphones that they would put over her tummy so I could hear more clearly. I was surrounded by music, even before I was born!” The residence of Maximiño’s great-grandparents and grandparents was built in a part of Abiquiú known locally as Los Silvestres. Over the years, it has come to be marked by an adobe wall and a rock retaining wall. I must have passed it thousands of times. That’s where Maximiño’s great-grandparents Maximinio and Rosana S. Manzanares raised their Grandpa Herman’s generation, where their Grandpa Herman and Grandma Ellie raised their Dad’s generation, and where they’re living now with their Mom and Dad. “When I was little, before I started school in Santa Fe, I spent a lot of time with my grandparents and familia as a whole in Abiquiú, and those are deeply cherished times in my life,” Maximiño continued. “In the spring, when the water was flowing through the acequia, my cousins and I would get little paper cups, and we'd catch tadpoles. And then we’d let them go, of course! Or, we’d race sticks down the ditch, or play around the apricot trees that our Grandpa Maximinio planted. There was no limit to our imagination. And there was always music, and so much love, and wonderful stories! All this made us feel so grounded.” After elementary school, Maximiño attended ATC, The Academy for Technology and the Classics, in Santa Fe, and after graduation matriculated into Stanford University in 2018. In September of 2019, after their first year of college, they moved from Santa Fe back to Abiquiú, together with their parents. Then, during Maximiño’s sophomore year, the COVID-19 pandemic globalized, and they took a leave of absence from school to return to Abiquiú and help their parents care for their Grandma Eleanor. “We were with my Grandma Ellie from October of 2020 until she passed away on August 1st of 2022,” Maximiño went on. “We got to spend almost another two years together, and those were some of the most sacred experiences of my life. We shared so many conversations, so many meals, and so many laughs. And she shared so much wisdom from her childhood and her life as a whole, including stories about her parents, her grandfather, and her extended family. She forever forged, strengthened, and cultivated my heart and spirit. It was immensely special for me to get to live together with my Grandma, Mom, and Dad in this way.” During this time, Maximiño and their family quarantined, masked, and practiced other safety protocols that the pandemic has necessitated in order to help keep everybody safe. After their grandmother’s passing, Maximiño started to participate more in the community doings while still continuing to mask and practice other COVID-19 safety protocols. For example, they and their Dad began participating with the choir. The Pueblo de Abiquiú Choir performs during masses for the community, whether for weekly mass, baptisms, weddings, quinceañeras, or funerals and burials. Maximiño’s Grandpa Herman led the choir for over 25 years, and now they and their father continue the tradition. “Actively participating in and leading the choir has constellated us to other musical doings in the Pueblo, including the Las Posadas, Christmas caroling with the youth, events with the Library and Cultural Center, and our Feast Days. Music is such a wonderful way to bring people together. You get to see everybody, you get to connect with the elders and the young ones and all the relatives in between, and you get to take part in feeling the pulse of the community and making memories together.” I was curious: what’s Maximiño’s major at Stanford? What are they studying? “I have a bit more than one full year left of school,” I learned. “I started in 2018, but because of personal and family circumstances, I've taken multiple leaves of absence. I've had a very non-traditional path through college, and it's been so beautiful because I’m getting this parallel experience of schooling in California alongside the education from my family, my community, and the land here. They all coalesce in an amazing manner. I intend to go back to school as soon as possible, complete my remaining coursework, graduate, and then return to Abiquiú.” “My major is in a program called CSRE, which stands for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity”, Maximiño explained. “CSRE majors get to choose one of many different concentrations, and mine is called IDA, which stands for Identity, Diversity, and Aesthetics. The IDA concentration focuses (through the lens of Critical Race and Ethnic Studies) on the ways that diverse racial and ethnic communities utilize various forms of artmaking and storytelling to perpetuate their cultures and to struggle for liberation of all people and the Earth.” “It has been an immense privilege to get to learn about and participate in the various doings and lifeways in El Pueblo de Abiquiú. All of my tías and tíos, all my primas and primos, and of course my Dad, have been so generous and gracious to share their knowledge, teachings, and understandings with me. For example, mi querido Mano Dexter Trujillo has been teaching me the songs that are done for our feast days. I am also learning more about the songs and prayers that we do when our elders and other dear community members pass away. I am forever grateful to every relative from the Pueblo for their teachings and their love. To be entrusted with these ways and with the responsibility of helping pass them on is such an honor.” Yes, I understand the appeal. Those traditions can easily get lost. Next, Maximiño told me about another project. “My Tía Victoria Garcia, who is the principal of Abiquiú Elementary, invited me to be a contracted Music and Art Teacher at the school. I enthusiastically accepted, and, between March and May of this year, I had the blessing and honor of teaching a little over 70 students from kindergarten to sixth grade. It felt especially cosmic because so many of my ancestors were teachers. My great-grandfather Maximinio, who I'm named after, was a teacher here in Abiquiú and Barranco. My grandmother's mom, Cordelia Laumbach Maés, was a teacher. My Tío Benigno “Bennie” Manzanares was a teacher. My Tía Patricia Manzanares-Gonzales was a teacher, professor, and administrator. They were all school teachers, yet, as my Grandpa Herman would say, ‘Everybody can be your teacher!” Such wise words were common in Maximiño’s family, and they shared more quotes that were passed on through generations. “My Mom has said: ‘It is not in the perfect moments we grow, but in the imperfect ones.’ My Dad has said: ‘Poco a poco, se anda lejos’ (Little by little, one goes far) and ‘We must live with respect, humility, consideration, and love’. My Grandma Ellie would tell my Dad: ‘If you can dream it, you can be it!’ And my Grandpa Herman told me, ‘If you want to be somebody special, be yourself!’ So, the wisdom that my parents and grandparents have shared with me has strengthened my roots, so that no matter where I go, I can be true to myself, true to where I’m from, and I can strive to move forward in my life with the utmost love for all of my present relationships; with the utmost respect for my ancestors; and with the utmost love and devotion for all future generations. In the words of James Baldwin: ‘The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe.’ We are responsible for all of them, including and especially those who we will not physically meet during our lifetimes.” I was so impressed with the way Maximiño acknowledged the guidance and support they received from their family. And not only accepted it but internalized it, made it their own to pass it on to others and future generations. And then I learned from Maximiño one of the stories of where this sensibility came from: “There's a story that my Dad has told me with regard to people’s ‘dones’ [gifts], and it’s about wisdom from the late Teresita Naranjo, an elder and incredible potter from Santa Clara Pueblo and a dear friend of my grandparents. One time Ms. Naranjo was over at my grandparents’ home when my Dad was about 14, and my Grandfather asked my Dad to play the guitar for her. So my Dad played for her, and she listened to him, and when my Dad finished his song, Ms. Naranjo said: ‘You have a gift, and that gift is not just yours. That gift belongs to your parents, and me, and the community, and the whole world. The Creator has entrusted you with this gift, and your responsibility is to make it the best that you can, so you can then share it and give it back to the world.’ My Dad and my Mom have raised me in that same way and spirit. All of the things that fill my heart, like music and dance and my family and our community and our culture, they are not just for me or for any one person. The gifts themselves are not solely ours, but, as I learned from my Dad’s story about Ms. Naranjo, what is ours is the responsibility to make them the best we can so we can share them back with the world respectfully, generously, and wholeheartedly.” Maximiño shared another great story with me. “Back in 2018, during my first year of college, I got to be a part of an a cappella group on campus called Stanford Talisman. They were founded on campus in 1990 with the intention of sharing music with compelling stories from around the world. A lot of their original repertoire is comprised of struggle songs from the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. So the origin of Talisman is rooted in struggles for Black Liberation, and over the past 35 years, the group has come to include music from all over the world. By the time I joined the group, a little before their 30th anniversary, we got to learn songs from Hawai’i, a song from Nicaragua, multiple Black American songs, and songs from India.” “Every year, Stanford Talisman goes on a tour for spring break,” Maximiño continued, “and for my freshman year, we went to India! So here I am, 18 years old, the first time I ever really traveled internationally… I remember being in awe when we were in Udaipur because its biome and climate are so similar to that of Abqiuiú. Even some of the homes in Udaipur reminded me of the adobe homes here. It was such a cosmic experience.”  ¡Cosntelaciones! An evening of stories through song in O’ga P’ogeh. Back row from right to left: Michael Burt, David Manzanares, Michael Manzanares, Mark Clark, Andy Kingston, Kanoa Kaluhiwa, Chief Sánchez, and Rubén Domínguez. Middle and front rows include Maximiño and members from Stanford Talisman 2024-2025. Image credit: Manzanares Family Archives “Then flash forward to this year, and one of my dear friends and fellow alum from the group reached out and let me know that the current group was going to come to New Mexico for their tour this year. So my family and I helped them coordinate their lodging and their itinerary. They stayed and performed in Santa Fe and Ghost Ranch. They also did an assembly at the elementary school in Abiquiú and shared some music in the Pueblo –– to me, it felt that everything came full circle. This coalescence of my upbringing, my family, my time at Stanford, my time with Talisman, and my time in the Pueblo, they all coalesced and got woven together.” Maximiño is such a good storyteller, I could have listened to them for hours. Here is another one: “I mentioned earlier that my Grandma Ellie would tell my Dad, ‘If you can dream it, you can be it!’ From my Grandma’s saying, my Dad and Mom co-created and co-cultivated the idea of dreamseeds.” “Just like we have seeds that we plant in the garden,” Maximiño continued, “so, too, do we have the seeds of our dreams that we can plant out into the world, and they each need their own tending in order to grow and ultimately come true. Of my dreamseeds, I have two in particular that I would like to share right now––one for El Pueblo de Abiquiú, and the other for the world as a whole. My dreamseed for the Pueblo is that our people, both individually and collectively, will do everything we can to learn as much as we can about who we are, about our truths, and about where we come from. It's from these truths that we can have a strong foundation and be the best relatives that we can be, not only to one another in the Pueblo but also to all our relatives in the greater Abiquiú community, and all of our relatives in the whole world!” What Maximiño next told me made me happy. Maybe there is hope, after all. “My family and I are vehemently against all forms of oppression. I'm thinking of our relatives in Palestine and in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in Sudan, and of all the people who are facing colonization and ethnic cleansing and genocide… So my dreamseed for the whole world is the liberation of all colonized and oppressed peoples and for me to do everything that I possibly can to help realize this collective dream.” “My Grandfather would say (and my Dad continues to say) that every day we give thanks for the Breath of Life. I want to become so fiercely intentional such that I live and act each day knowing that every breath I take is not just mine. With every breath that we’re given, may we all come to understand the next right things to do, and may we then do them, even when they are scary, uncomfortable, or new. “May I become more grounded in my body. What is my whole body feeling? What is it receiving? What is it giving, and how does it fit into this beautiful, intricate, infinite multiversal web that we're all a part of?” Important questions indeed, worthy of contemplation, and somehow surprising to come from a young person. More wisdom and less Ego – that’s what I usually expect from older people, and often I’m disappointed. To meet somebody who isn’t preoccupied with their own success, who doesn’t dream of becoming famous but of serving their community – this doesn’t happen all that often. And yet, I’m not surprised to find such a person in Abiquiú, which has plenty of unconventional, community-oriented people.

We will continue this conversation at a future time; I’d like to learn more about the traditional Matachine dances, and Maximiño will consult with the elders who have made their revival in Abiquiú possible about what can be shared, as well as the most respectful and considerate way to share these stories. And I definitely want to hear more stories from Maximiño’s abuelitos. It was such a pleasure to listen. I know you have many commitments, Maximiño, and I’m grateful for the time you gave me. May all the flowers keep blooming for you! By Peter Nagle

5/30/25 May has been a very positive month for stock markets here, and in Europe as well. But headlines about tariffs are still roiling equities and even bonds. It’s amazing to me that the wars in Gaza and Ukraine are not causing more difficulties for markets. I guess investors don’t care what happens there. I don’t know about you, but I definitely do. Gaza, Israel, and the West Bank especially for me. I’ve been to Israel/Palestine many times in the last 20 years. 16 to be exact. Most people here have little understanding of what’s happening there I have found. Maybe I’ll write about my experiences there sometime, and the actual causes of the conflict, and the genocide going on in Gaza, in my view. For now though, let’s stay with investments. I suspect this will be a rocky summer in the investment world. There are the tariffs, which are very destabilizing. And I believe Ukraine will become more of an issue globally as our President realizes he’s being played by Putin. We will have to escalate to force Putin to the negotiating table. Right now he believes he’s winning the war, so why should he negotiate? The enormous cost in lives and resources doesn’t phase him one bit. I’m generally a pretty conservative guy when it comes to investments. That’s why I like annuities where they fit - they’re guaranteed not to lose money, and they can either pay you for life, or build up in value. And they’re tax deferred! They have a lot of advantages for the right situation, which is what I help people figure out. Where they fit, they’re unbeatable. There’s a place for all kinds of investments in your portfolio. Diversification is a sound investing principle. But as we get older, investing conservatively becomes more and more important. Especially in these unprecedented times. Have a great June. The weather here is just wonderful isn’t it? **************************************************************************** I provide financial advice to individuals in our Abiquiu community at no charge as a way of giving back. If you have questions in that area feel free to contact me. I’ll do the best I can to help you sort through the issues. Peter J Nagle Thoughtful Income Advisory Abiquiu, NM 505-423-5378 (mobile) [email protected] 2nd Annual Abiquiú Gathering of Artisans Returns June 14–15 with Art, Flavor, and Community5/28/2025 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Becca Fisher Email: [email protected] Website: abiquiuartscouncil.org 2nd Annual Abiquiú Gathering of Artisans Returns June 14–15 with Art, Flavor, and Community ABIQUIÚ, NM – The Abiquiú Arts Council is proud to present the 2nd Annual Abiquiú Gathering of Artisans, taking place on Friday and Saturday, June 14 & 15, from 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM at the Rio Arriba County Rural Event Center in Abiquiú. This vibrant, juried art show features 22 talented artists from across Rio Arriba County, NM, offering a unique opportunity to experience the depth and diversity of Northern New Mexico’s creative spirit—all in one stunning location. Visitors can expect a wide variety of fine art and hand-crafted work, including painting, pottery, jewelry, textiles, folk art, and more. Each artist has been carefully selected to represent the exceptional talent rooted in this region. Adding to the festivities, New Mexico favorite Chicano Dog will be on-site both days, serving up mouthwatering New Mexico-style hot dogs, frito pies, chips, drinks, and more, making this event a true feast for all the senses! The Abiquiú Gathering of Artisans is produced by the Abiquiú Arts Council 501(c)(3), a passionate, volunteer-run nonprofit dedicated to uplifting artists and enriching the cultural life of our region. The Council is also the organization behind the beloved Abiquiú Studio Tour, held annually every October, which draws art lovers from near and far to explore artist studios nestled throughout the iconic Abiquiú landscape. Admission is free, and the event is easy to find: From US-84, turn onto NM-554 and drive 1.3 miles to the Rural Event Center—just follow the signs and flags! Join us for a joyful weekend of art, food, and Northern New Mexico pride. Support your local artists, discover new favorites, and enjoy a day in one of New Mexico’s most inspiring communities. Visit www.abiquiustudiotour.org/abiquiu-gathering-of-artisans-artists/ for more details! New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham is urging counties across the state to ban fireworks and has ordered a task force to come up with short-term emergency measures to address the ongoing drought and mounting wildfire risk, her office announced on Wednesday.

The governor issued an executive order declaring a state of emergency last Thursday, which unlocks funds to help address the drought. It also directed the New Mexico Drought Task Force to meet, which it did Wednesday, to come up with ways to coordinate response efforts across more than 10 state agencies, according to a news release. New Mexico is currently experiencing some of the worst drought conditions ever recorded amid long-term predictions that the state could lose 25% of its water supply over the next 50 years. Snowpack, particularly in the southwestern part of the state, is at record lows, and about 87% of the state is experiencing drought conditions. Meanwhile, local, state, federal and tribal governments across New Mexico have imposed various levels of wildfire restrictions, citing the ongoing wildfire risk. A New Mexico State Forestry website compilation of those restrictions lists 38 jurisdictions that ban fireworks, campfires or impose other measures. “Despite some spring precipitation, almost all of New Mexico remains in conditions that threaten water supplies and elevate fire danger,” Lujan Grisham said in a news release. “The State Forester has enacted fire restrictions for high-risk areas, but we can’t stop there. This executive order ensures that we act decisively to conserve water and lessen our exposure to wildfire risk.” In its Wednesday meeting, the Drought Task Force, led by New Mexico State Engineer Elizabeth Anderson, began coming up with a list of short-term measures to reduce fire risk and help those affected by the drought, which it needs to have in place by July 31, according to the governor’s office. The task force also is tasked with compiling and sharing emergency and other funding sources to help families and governments respond to the drought. “New Mexico’s river basins have seen below average precipitation this year, and our reservoir levels are among the lowest on record,” Anderson said in a news release. “These conditions clearly justify emergency action.” As July 4 approaches, the governor wrote that she urges “New Mexico’s counties, municipalities and local governments to consider implementing firework bans pursuant to the Fireworks Safety and Licensing Act…as well as any other appropriate fire prevention measures that they may legally enact.” The National Education Association of New Mexico sent a letter Tuesday to the Española School Board asking for a “full and detailed explanation” of who authorized Española Valley High School’s directive to teachers last month, ostensibly as part of a standardized test, to collect students’ immigration statuses.

The union also accused the district of deleting the information it collected, which leaders said amounted to “destruction of evidence during an open union investigation.” That prompted the union to file a Prohibited Practice Complaint with the Public Employee Labor Relations Board of New Mexico. “We fear not only the impact these actions have on our membership but the students as a whole,” the union wrote in the letter. “We are writing to seek your help to rectify these matters. The district and staff deserve to have a school district that is lawful and free of fear and intimidation.” A teacher posted on Reddit on April 21 that they had reached out to the union after teachers were asked to collect the data as part of the WorkKeys standardized test, an assessment that the ACT created to measure job readiness. An ACT spokesperson told Source New Mexico last month that it never seeks that information, saying its collection is “not a requirement for taking our exams and is not information we collect or use in any way.” The letter calls on the school board to, by June 2, provide copies of all internal communications and documents regarding the directive; an “explanation of the rationale” for later deleting the collected data; and confirmation about whether the data was ever transmitted to ACT, Inc. In an interview Tuesday with Source New Mexico, NEA-NM spokesperson Edward Webster said the district needs to “stop playing the game” with the union and teachers about what happened and be transparent about what happened and why. Eric Spencer, the Española superintendent, did not respond to an email Tuesday afternoon from Source New Mexico. The school board meets this evening at 6 p.m., but the matter is not on the agenda. School board president Javin Coriz did not respond to a request for comment Tuesday afternoon. The effort to collect the data occurred amid fears that that information could be turned over to federal immigration authorities, and a few months after border patrol agents boarded a Las Cruces swim team’s school bus. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham recently said in an interview with Source that the state is continually beating back efforts by the federal government to collect private data about New Mexicans, including immigration data. The Legislature also passed several bills aiming to keep immigration data out of federal hands. The state Health Care Authority also recently denied a request from the federal Agriculture Department for cardholder data of those who receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program assistance. Courtesy of the CDC COUNTY NEWS RELEASE & the Los Alamos Reporter

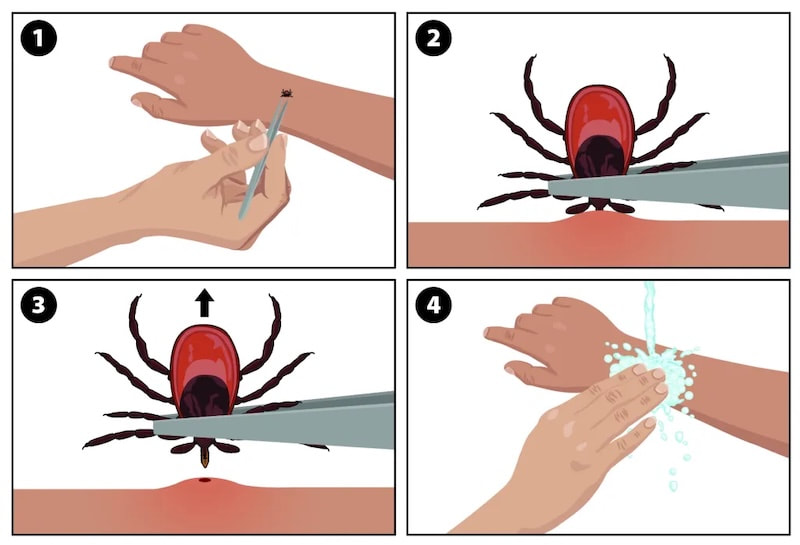

CDC COUNTY NEWS RELEASE If you find a tick attached to your skin, remove it as soon as possible. Do not wait to go to a healthcare provider to remove the tick. Delaying tick removal to get help from a healthcare provider could increase your risk of contracting a disease spread through tick bites, known as tickborne diseases. Follow these steps to remove a tick:

A word of caution: Do not use petroleum jelly, heat, nail polish, or other substances to try and make the tick detach from the skin. This may agitate the tick and force infected fluid from the tick into the skin. Check out the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tick Bite Bot – A tool to assist people in removing attached ticks and seeking health care, if appropriate, after a tick bite. The online mobile-friendly tool asks a series of questions covering topics such as tick attachment time and symptoms. Based on the user’s responses, the tool then provides information about recommended actions and resources. Find the tool on the CDC website: https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/after-a-tick-bite/index.html How ticks spread disease Ticks transmit pathogens that cause disease through the process of feeding:

Symptoms of Tickborne Diseases Many tickborne diseases can have similar signs and symptoms. If you get a tick bite and develop the symptoms below within a few weeks, see your healthcare provider. The most common symptoms of tick-related illnesses include:

Men are menning. I have receipts. By Zach Hively A little while back, I wrote a style guide called How to Dress Yourself More Better for Tango, My Man—and Also for Life. It wound up being controversial, especially (or entirely) among men. In this authoritative guide, I called out everyone who thinks—and I paraphrase—that an outfit is suitable for special occasions if it was once launched out of a T-shirt cannon. And I do mean everyone. Even if the only people who think so are men. Many men, it turns out, do not want to hear that they present as the fashion equivalent of Great Value garbanzo beans. And that’s when they’re trying to dress nice. You would think this helpful guide might have landed better coming from me, speaking with the authority that extends from being a man. And you might be right. Maybe the response I got was the best-case scenario. Imagine how badly these many men might have reacted if I had written that headline as literally any other type of human person. But still, I didn’t expect any real backlash, no matter how adamantly I suggested men might want to tuck in their shirts—shirts with buttons, even—if they wanted a chance at dancing with anyone at all. I am not used to being told I am wrong. Neither, it seems, is any other dude bro man. Did you know, for instance, that writing a set of “time to man up” tips means it’s open season on your chosen hairstyle? Unless you are a woman, or possibly a member of a non-dominant culture, your answer is almost certainly “No, I did not know that.” I felt it only appropriate to respond to this follicle-challenged man-presenting individual. I replied, “I almost wrote a section on waxing our bald spots and receding hairlines, but instead I decided not to kick my fellow men in the genes.” But I soon stopped responding to the trolls. Especially when they’ve already proven that they don’t read past the social preview image. A demonstrated lack of reading comprehension does not generally stop these men from forming—and voicing—opinions. Did you know, for further instance, that trying to help your fellow man level up (both affordably and actionably) also opens you up for critique on your physique? Even when your physique is literally out of sight under a suit jacket in the provided photographs? Even when the function of a suit jacket is to make any man-shaped person instantly more man-shaped by hiding his actual body so no one can tell exactly how much he doesn’t work out? Ah, and then we have those who just need to feel better about their manly selves by pointing out how other people are trying to feel better about their manly selves—because commenting on an internet post is simpler than dressing well and expressively: Perhaps this man-presenting person best utilized brevity to demonstrate that he is confident enough in his manhood not to take good care of it: Now, I have been acculturated to think that I cannot ever be wrong about anything, ever. Same as all these man-presenting folks. But their commentary was enough to make me start to doubt myself. Was I … for the first time in my life … a man in the wrong? Fortunately, no. Men are awful, but not me! At least not this one time. And how do I know? Because many of the people smarter than men are women, and not a single one of them saw fit to demean me in a public social media comment. Their perspective is more valid than the men-type people’s, because a great many of them appear to have actually read the piece.  “Not shallow! At a larger festival when trying to figure out who I might want to dance with, eight times out of 10, the man with a tucked in pressed shirt and a belt is the better dancer. A sport coat—always. Two times out of 10 the dude in shorts and a T-shirt is wonderful.” (Yes, the bar is set below “wears a belt.”) And some women-identifying readers offered men more ideas I wish I’d thought of first. However, just because every woman with eyes and a sense of smell agrees with me—that man-presenting people who shower and wear clean clothes are more appealing—doesn’t mean I’m 100% right. I have been wrong about a few things. Such as presuming men will never change. One man sent in a picture that he—possibly for the first time in his adult life—wore slacks instead of jeans to a formal event. Another man shared advice for finding quality used suits. Yet another conceded I was right, failed entirely to attack my physical attributes, and instead just shared his own stance in a healthy, non-confrontational way. In this process of obsessively lurking on other people’s posts to see how else they might support my ideas or take cheap shots at my hair, I started to realize something: This behavior is what women and other not-men risk dealing with every single time they venture onto the internet, or into public, or exist.

I suspect that these oppositional men were less incensed by my headline, if they even read it, and more peeved that women were out there agreeing with me that men can do better. Which we do. We, on the whole, really kinda suck. I suggested originally that men could do better by wearing clothes that fit. But I need to amend that. Men: we need to do better ALL THE TIME, WITH EVERYTHING, EVER. Yeah yeah, hashtag not all men. But all men. All of us, and often. So I leave my fellow man-presenting people with one final thought for you all to get mad at me about. We all know that universal problems don’t beget universal solutions until they happen to a man. Women have been dealing with this crap forever. But now it’s happened to me. So let’s cut it out. Enough is enough. Not even a tailored suit can make us look better when we resort to tearing other people down. [Note: all screenshotted responses were left on public posts, so the commenters are receiving greater anonymity here than they could reasonably expect.] By Felicia Fredd

I’ve seen very few fatally over-watered garden plants in New Mexico. It tends to occur with new plantings, a time of more enthusiastic watering, but even then it seems limited to ‘touchy’ desert plants - young yucca and native sagebrush, for example. What I do see is a lot of is chronically under-watered plants. When people show me an ailing plant, and ask “What do you think is wrong?”, I’m almost always looking at long term drought effects: stunted plants with small off-color leaves, and little new growth. There’s often a physical history you can ‘read’ on the plant of multiple near deaths from sun scalding, twig and branch die-off, etc., and so while a plant may have received some ‘extra’ water, it clearly wouldn’t have been enough per watering, and far too much time between waterings. It can be such a source of pain that I think some would almost rather know a plant is suffering from an incurable disease. Yes, nutrient deficiencies and diseases are common, but even many of these problems can be traced to insufficient watering. Good news: watering issues are easily testable without sending out to a lab. Water better using deep water cycling for 2-3 weeks, and see if there’s a good response. That’s the test. Definitely do this before before turning to ‘soil amendments’ or fertilizers, and never fertilize a dehydrated plant: https://extension.unh.edu/resource/fertilizing-trees-and-shrubs-fact-sheet There are so many things that can be said about plant needs, so many exceptions to general rules, and so many disasters that will remain a mystery, but assuming your plants are appropriate for given light and soil conditions, aren’t sitting in a concrete pocket of caliche, aren’t getting peed on by the dog, etc., their most basic need is water, which they require for the following reasons: Photosynthesis Water is an essential ingredient in photosynthesis, the process by which plants use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to capture energy in the form of sugar (glucose). It is also the process responsible for storing all the energy we extract from fossil fuels, crops, and all of our food. https://www.ocean.washington.edu/research/gfd/has222-archive/lecture7B-06ClaraCarboncycleOutline.pdf Transport of Nutrients Water moves nutrients and minerals from the soil into the plant through its roots and up to the leaves. Water is the delivery system that allows plants to absorb, transport, and use nutrients. Without it, nutrients are unavailable - even if they're present in the soil. Water stress also reduces root activity, further blocking nutrient uptake. Maintaining Turgor Pressure Turgor pressure is the force exerted by water inside the central vacuole of plant cells, pushing the cell membrane against the rigid cell wall. It’s maintained when cells are full of water, creating internal pressure that keeps the plant upright and strong and enabling new growth. Without it, plants can’t grow effectively - even with nutrients and sunlight - because turgor pressure helps move sugars and other compounds through the phloem, the plant's nutrient transport system. Cooling Plants lose water through pores (stomata) in their leaves during transpiration. This helps cool plants while pulling more water and nutrients up from the roots. “A fully grown tree may lose several hundred gallons of water through its leaves on a hot, dry day. About 90% of the water that enters a plant's roots is used for cooling under warm dry conditions.”https://my.ucanr.edu/sites/marinmg/files/152980.pdf Biochemical Reactions Water acts as a solvent inside the plant. Nearly all of a plant’s biochemical processes require water to occur. Deep Watering Cycling Deep watering is equivalent perhaps to a good hour long rain, or about an 8” depth of soil saturation. It is much more than most people imagine is necessary per each watering. For general maintenance, and especially when talking localized drip irrigation timing, basic requirements are usually expressed as a few gallons a week for smaller plants, a few gallons more for larger shrubs, and about triple more for larger trees (tree root zones extend over a much larger area as well). However, those numbers in gallons, across X number of days, aren’t fully useful since they don’t account for specific plant needs, or the changes in temp, humidity, wind evaporation, etc., that result in faster/slower soil drying per week. The true amount necessary - which can only be determined by the visible health of your plants - will be a combination of deep watering (8” depth is a good consistent measure) followed by a drying cycle. The time to water again is when the top 2 inches of soil are again dry and crumbly, and certainly just as soon as you see leaf wilting - even if it’s in the middle of a hot day. During the drying period, oxygen and other gases flow back into soil pore spaces which plants need at their root zone for energy metabolism. Soggy, oxygen poor, soil is referred to as anaerobic or anoxic (not exactly the same thing). In any case, plants adapted to low oxygen soils - wetland plants, for example - can tolerate both low oxygen levels and the types of microorganisms found there. Xeric dryland plants cannot. So, deep watering forces oxygen and gases out, and a drying period let’s them back in. It’s the optimal cycling that brings everything into balance, and allows the most effective use of water. Shallow watering, such as when you lightly wet a soil surface on a hot day, does little more than force a desperate plant to develop shallow surface roots that are then exposed to more extreme heat and deadly drying. The term ‘over-watering’ is bit of a misnomer to me because it’s really a matter of under-oxygenating soil as part of a wet/dry cycle. I don’t worry about applying too much water as long as I get the second part right. I probably should be more concerned about over-watering because heavy flooding can cause problems with soil compaction and nutrient leaching, but that’s another story for another day... |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed