|

The tax and spend legislation going through the U.S. Congress could reverse New Mexico’s raises for health care providers who serve Medicaid patients called “provider rate increases.”

The unsettled fate of the Medicaid provisions amid rulings against their inclusion by the U.S. Senate parliamentarian leaves New Mexico waiting to see what its fate will be as a state with a heavier stake in Medicaid than any other. In January, New Mexico started paying health care providers who serve Medicaid patients at 150% of the rate paid by Medicare, with the goal of providing more people primary, maternal and behavioral health care. Legislative Finance Committee Director Charles Sallee told state lawmakers on Thursday that the U.S. Senate’s version of the bill would require states to bring hospital rates down to what Medicare pays. “That would be another big hit,” Sallee said at the LFC’s meeting in Taos. “The hospitals just barely got this program up and running.” The expanded payments started going out in the last few months, Sallee said, and have helped stabilize rural hospitals in particular. But it’s “a big unknown” if those payments will be upended, he said. Sallee said his staff is researching a concern raised by the state Health Care Authority, which runs the state Medicaid program, that these payment caps would apply to other kinds of services like primary care, maternal care and behavioral health care. He said he has asked to meet with U.S. Sen. Ben Ray Luján’s office next week about the issue. New Mexico has allocated more than $2.2 billion for provider rate increases over the past couple of years, Sallee said. “That would go away,” he said. “So that has significant implications for our health care system going forward.” Sen. Linda Trujillo (D-Santa Fe) asked why the federal government cares if New Mexico pays higher rates, and whether it has anything to do with matching what states pay out. Sallee said yes, particularly in states like New Mexico that have expanded their Medicaid programs. “That’s the majority in Congress’ thinking: ‘Why should we pay so much?’” he said. Sallee said he expects to update state lawmakers again about the federal budget in July.

0 Comments

While dozens of New Mexico acequias continue reckoning with damage from natural disasters over the last three years, they are making progress, according to officials helping them navigate multiple layers of bureaucracy.

Disasters like the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire near Las Vegas in 2022, along with the South Fork and Salt fires in Ruidoso and the Rio Chama Flooding in Rio Arriba County last year, resulted in damage to 150 acequias, according to Paula Garcia, executive director of the New Mexico Acequia Association. That amounts to about one-sixth of the state’s roughly 900 acequias. Garcia gave a presentation to members of the Legislature’s interim Water and Natural Resources Committee, which is meeting Tuesday and Wednesday in Las Vegas, a town of about 12,000 that continues to grapple with the aftermath of the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire, particularly when it comes to post-fire flooding and potential drinking water contamination. The presentation occurs as President Donald Trump’s administration mulls deep cuts to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the potential end of disaster declarations that keep certain emergency funding streams flowing to individuals and public entities. It also comes after dozens of people were fired locally from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a federal agency that funds emergency watershed repair and other programs acequias rely on. Last week, Western governors agreed to explore formalizing inter-state partnerships to address the aftermath of post-fire flooding, a concern they dedicated an entire panel to during the annual Western Governors’ Association conference in Santa Fe. Agriculture that relies on acequias in and around the burn scar remains largely halted more than three years after the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire, Garcia said, and every rainstorm brings the threat that acequias will flood or fill with silt that flows off fire-scarred mountainsides. But she said her nonprofit organization and state government agencies are making progress when it comes to finally untangling a complicated federal bureaucracy that was initially unfamiliar with acequias and is still inflexible when it comes to ongoing flooding. “I would like for FEMA to clean up the bureaucracy and red tape, but we’re managing it now,” Garcia said. One major hurdle acequias faced concerned upfront costs they must produce before work can be completed, Garcia said. Even though state or federal agencies reimburse most or all costs, even modest upfront costs are often insurmountable for the small, volunteer-led irrigation canals. As such, more than 100 acequias statewide have sought help from the NRCS’ Emergency Watershed Protection Program, Garcia said, largely because that program allows acequias to offload the paperwork to a local sponsor like a county or a local soil and water conservation district. Thanks to a partnership between FEMA and state agencies, the state Transportation Department has entered into agreements with about 70 statewide acequias, including 54 in the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire burn scar, to allow the DOT to remove debris from silted-in acequias. FEMA then reimburses DOT for the associated costs. About 67 Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon acequias also have pending claims with the FEMA office overseeing a $5.45 billion fund aimed to compensate victims of the fire, according to Garcia’s presentation. Garcia called on the state Legislature to find ways to help acequias pay the upfront costs and to formalize a system to remove debris from acequias. She also called on the state to create its own version of the Emergency Watershed Protection program, which is popular among acequias and also reliant on an agency undergoing staffing cuts. According to various reports, NRCS laid off at least 35 people locally. “NRCS is a really wonderful agency, and it’s tragic to see those cuts,” Garcia said. “I think there’ll be implications for these programs if those cuts continue.” By Peter Nagle 6/30/2025

This is the July newsletter. We took June off to travel to the Northeast for my wife Joy’s daughter’s wedding. What a wonderful day! While there we visited with other family and friends in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Mass, including the Cape. it was a very fun trip! So, how have things gone in the markets? Quite well actually. Equity markets are at historical highs. Bonds have held steady. Interest rates are largely unchanged. It sure seems time for the Fed to lower rates. The fear that Chmn. Powell has had is that the tariffs Pres. Trump introduced will re-accelerate inflation. There is a danger that could happen, and it’s too early to tell whether they will, but so far they have not. It’s less that 6 months though so vigilance is still the word around here. There are reasonable arguments both ways on this, and I won’t bore you with the details but it appears so far that the tariffs have not led to the end of the world as some of us feared. This is likely because the President wisely pulled well back from the extreme approach he initially took. If he had tried to force those extremely high tariffs on other countries, I think the markets would have gone in the opposite direction than they have. I think he figured that out and rapidly changed course. Looking forward, markets never go straight up so it seems reasonable that we’ll see a decent size correction sometime in the next 3-4 months. 10 - 15% is my guess. And they are scary when they happen. But this could actually present a good buying opportunity if it happens. So I would keep some powder dry for that probability. As I’ve said before, a balanced approach generally works best. I like annuities for a part of your portfolio - they’re guaranteed not to lose money, and they can either pay you for life, or build up in value. And they’re tax deferred! They have a lot of advantages for the right situation, which is what I help people figure out. Where they fit, they’re unbeatable. There’s a place for all kinds of investments in your portfolio. Diversification is a sound investing principle. But as we get older, investing conservatively becomes more and more important. Especially in these unprecedented times. **************************************************************************** I provide financial advice to individuals in our Abiquiu community at no charge as a way of giving back. If you have questions in that area feel free to contact me. I’ll do the best I can to help you sort through the issues. Peter J Nagle Thoughtful Income Advisory Abiquiu, NM 505-423-5378 (mobile) [email protected] Courtesy of Archaeology Southwest Guest post by Istara Freedom (May 24, 2023)—My name is Istara Freedom. Born in Arizona, I spent my first 12 years in the Southwest, in the Four Corners area, around what is known as Bears Ears and Moab, Utah. We moved to the coast, and many years later, I discovered the long history my mom’s family has in New Mexico. Growing up, I wasn’t very aware of my mom’s complete heritage or the long, complex story of her and other Indigenous and European—primarily Spanish and Basque—peoples in the making of the Southwest. At one point, I became aware that my mom knew she was part Pueblo. Once on a visit to Abiquiu and the Abiquiu Inn and bookstore, I was drawn to look at books specific to the village, and quickly noticed my mom’s family surnames were prominent in several books. As I got to know Abiquiu better, I learned about the village and the Pueblo, which I had no idea was as rich, dense, and layered with a story that was formed before this country even became America as we know it. This story is layered with Spanish colonists and Indigenous Tribes, both local and migrating, and part of the vast undertaking that formed New Spain, then New Mexico, a history not to be covered here. I now know that this complicated narrative is a huge part of my family, my story, and the creation of my DNA. On a trip to Abiquiu, I learned about the Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center, and I began in-depth research with the extensive records collection there. In time, I got my mom to submit her DNA for analysis, which showed an unsurprising combination of about two-thirds Spanish and one-third Native American. One Abiquiu visit coincided with talks being given on New Mexico genealogy and a specific DNA study of Abiquiu residents, for which I was able to submit my Mom’s DNA. The studies indicate that her mtDNA comes from the Pueblo people, meaning that her earliest known female ancestor on this continent was likely of Pueblo descent. As it turns out, my family line, originating with the Spanish colonists, spent over 150 years in Abiquiu and surrounding areas in Rio Arriba County. I learned the term Genízaro, as well as how to pronounce it—heˈni zaɾo. Abiquiu is defined as a Genízaro village. Genízaros include individuals from many Native American Tribes enslaved by Spanish colonists or by other Tribes during raids and skirmishes. “They are living heirs to Native American slaves. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Native American women and children captured in warfare were bought, converted to Catholicism, taught Spanish and held in servitude by New Mexican families. Ultimately, these nontribal, Hispanicized Indians assimilated into New Mexican society.” (All Things Considered, NPR, 12/29/2016) The village of Abiquiu is located in Rio Arriba County. In every direction, there is evidence of human habitation and remnants of Indigenous and Pueblo peoples layered and dispersed in the cliffs, the hillsides, and even the village—both ancient and with some modern additions, such as Bode’s General Store and gas station. The ancient pieces of human history constitute an incredible timeline of continuous habitation for unknown millennia, from mesa top agriculture, cliffside pit houses, old Pueblo dwellings, and defensive natural fortress areas used by strong Native warriors to protect themselves from marauding Tribes and later, the Spanish settlers. My ancestors were probably on both sides of these conflicts. The Rio Chama runs through the entire area of Abiquiu, alongside US 84, and crosses under it through Barranca. Whenever I have seen the Chama, I have felt a definite yet indefinable emotion. It made more sense when, in the course of my research, I came across a record of a petition for land along the Chama by my great grandfather in the early 1800s. Although I could not find any records of an outcome to the petition, I can only imagine the dire importance of this water to my ancestors and all peoples who lived in these areas since the beginning of human habitation. In the Merced del Pueblo de Abiquiu, there is a plaza, with the main features being the St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Parish and more recent structures, including the Georgia O’Keeffe home and the tiny library that also houses the cultural center. Surrounding the plaza are residential dwellings from old and crumbling adobes to a modern, vintage mobile home. There are only dirt roads here, no street lamps, crosswalks, or signage. On some roads, there are cattle crossings, and in two places, there are Catholic Penitente Moradas, features that are specific to New Mexican Catholics, and two cemeteries, one primarily for the Pueblo, and one for the village. The layering and the impacts of dwellings, reverence, warfare, detribalization, and settlement are dense, as it seems the dust never completely settled between events that happened here to make it what it is today. At one point in my research, I found my ancestors lived at an archaeological site called Las Casitas near El Rito, New Mexico, a small town not far from Abiquiu. The adobe site of Las Casitas lies north of Abiquiu in the El Rito Valley. It was founded in the first years of the 1800s by my forebears along with other families. My family’s connection to the site has not been revealed previously, and the builder and residents were described just a couple years ago as unidentified (Snow 2020). The site was partially excavated and studied by archaeologist Herb Dick and a crew from the Museum of New Mexico, but has not been well reported (Dick 1959). My great granny Sotela Martinez, and great granddad Juan Pablo Romero lived at Las Casitas. His father, Lorenzo Romero (my great, great-grandfather), is listed in the 1850 census for the area. My great, great-grandmother Concepcion Lopez was also living at Las Casitas, along with other aunts, uncles and cousins. I visited Las Casitas with Paul Reed, who subsequently invited me to share my story in this post. Las Casitas is now part of the Carson National Forest, and it was a very strange feeling, like being in a family home that has been raided, without much left for the remaining family to recollect. I felt moved with emotion, distance, emptiness, and a wonder that is hard to describe. I feel the pangs of my forebears, as reflected in my life growing up and who I am today. At St. Thomas Parish, in Abiquiu, the annual Feast Day occurs every November. The procession begins in the Plaza, enters the Parish, then returns to the Plaza and finally moves to a private home on the Pueblo. A central aspect to this day is the young women and girls dressed in colorful attire, representing the young Indigenous women and girls that were marketed in the village of Abiquiu, allegedly saved or purchased by the Spaniards from warring Tribes and ransomed in the village marketplace for wealthy settlers to use as servants and wives. The resulting children are the ancestors of the local Genízaro community. Each of us that comes to the Feast Day for our Ancestors is here to learn, accept, forgive, and care for what was important to them. We come to recollect the beauty, understand the loss and sorrow, and protect the land. We come to soothe their collective pain, losing tribe, identity, and children, and fighting in so many wars. Now we are fighting to reclaim our understanding and our identity and to give honor, recognition, and life to those that gave us ours. Acknowledgments My inspiration for this work comes from my mom, Estella. My research has greatly benefitted from the scholarly efforts of several individuals who have been pursuing Genízaro history for many years, including Moises Gonzales, Bill Piatt, and Gary Medina Cook, among others. The recent book Slavery in the Southwest: Genizaro Identity, Dignity and the Law by Piatt and Gonzales has been most helpful. Gary Medina Cook’s recent film The Genízaro Experience is a wonderful exploration of Genízaro history and social identity. I also want to thank the Trujillo family and many other folks in Abiquiu for welcoming me. I was blessed to be welcomed to the Santo Tomas feast day by many residents of the Pueblo de Abiquiu. Sharon Garcia, librarian at the El Pueblo de Abiquiu Library & Cultural Center helped me in many ways with my research. Thanks to Paul Reed. Lastly, I want to thank Carmen López, Mayordomo of the St. Thomas Parish, for her permission, compassion, and embrace in reverence for our mutual Ancestors on sacred land in Abiquiu during the feast day ceremonies. Link to Istara's book on Amazon. Location: The wildfire is in the Jemez Ranger District, near the northwest boundary between the Valles Caldera National Preserve and the Santa Fe National Forest, adjacent to Forest Road 144 and Twin Cabins Canyon.

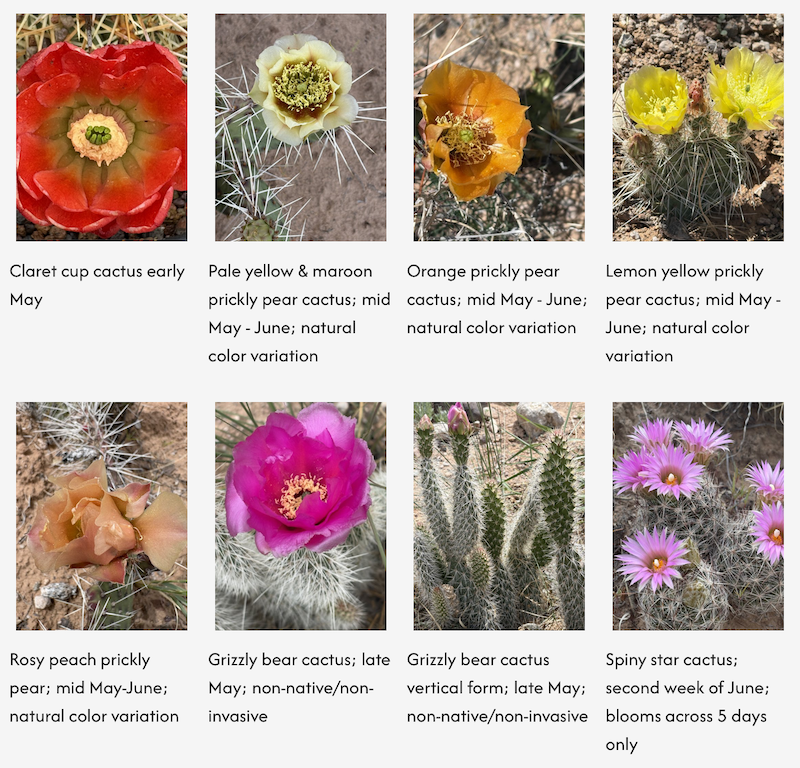

Start Date: June 23, 2025, at 1:00 p.m. Size: 40 acres Containment: 10% Cause: Under investigation Vegetation: Burning in oak brush, ponderosa pine, and Douglas fir. Resources: 40 personnel Overview: Fire crews are actively managing the 40-acre wildfire using full suppression tactics. Currently, the wildfire does not pose a threat to people or property. Highlights: Fire line around the perimeter held overnight. This morning the wildfire reduced in complexity transitioning to a Type 5 incident. A Type 5 incident is the lowest level of complexity in incident management, typically manageable with minimal resources. Fire crews continue to mop up, which means extinguishing and removing burning materials near control lines. Currently, 40 feet from the fire line has been mopped up around the fire perimeter. Weather: Conditions will be mostly sunny and clear on Friday and Saturday, with showers and thunderstorms expected on Sunday and continuing into next week. Safety: The health and safety of firefighters and the public are always the highest priority. Please avoid the area while crews manage the Twin Cabins Wildfire. Drones and firefighting aircraft are a dangerous mix and could lead to accidents or slow down wildfire operations. If you fly, we can’t. Smoke: Smoke may be visible to communities along New Mexico State Road 96 and New Mexico State Road 4. Fire Information: Contact Claudia Brookshire, Public Affairs Officer, Santa Fe National Forest Phone: 505-607-0879 (available from 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.) Email: [email protected] Links: Santa Fe National Forest website, New Mexico Fire Info, Inciweb, and Santa Fe National Forest social media (Facebook and X). About the Forest Service: The USDA Forest Service has for more than 100 years brought people and communities together to answer the call of conservation. Grounded in world-class science and technology– and rooted in communities–the Forest Service connects people to nature and to each other. The Forest Service cares for shared natural resources in ways that promote lasting economic, ecological, and social vitality. The agency manages 193 million acres of public land, provides assistance to state and private landowners, maintains the largest wildland fire and forestry research organizations in the world. The Forest Service also has either a direct or indirect role in stewardship of about 900 million forested acres within the U.S., of which over 130 million acres are urban forests where most Americans live. By Felicia Fredd The cactus pictured above is Escobaria vivipara, or Spiny Star cactus—a species that grows right here in Abiquiú, NM. According to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, it's actually the most widespread cactus in North America, and yet I had never seen it in my life until two weeks ago, when I stumbled upon a field of them in bloom. The color you see in the photo above is not enhanced; it is the actual deep rich color that appears for the first two hours of the flower’s opening. After that, the petals soften into a silky wash of bright pink and silver. It’s one of the final cactus blooms of spring.

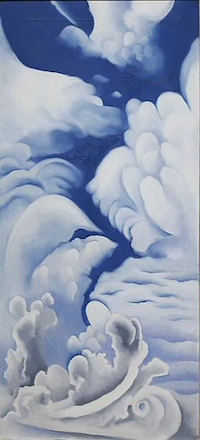

The Cholla bloom, occurring now, will mark the end of this year’s cactus flower season. It is now too hot and dry for them to expend the energy. As I write, I’m waiting for the big rainstorm (that one was supposed to begin yesterday) to finally provide the deep watering even my cacti need. I don’t have irrigation water for my desert garden project in the badland foothills of Abiquiú, where efforts so far have been a labor of observation, small moves, and more observation. I have found native plants I can work with, and important structural considerations I can provide to help native plants grow here, but it’s still tricky. In previous articles, I’ve covered a few of the many reasons why native plants are so special, but it’s also important to acknowledge that even the most rugged natives can be hard to grow. Plants are just so bloody complicated. Sure, you’ve seen things growing in cracks in the sidewalk, or dangling from cliff faces, but it’s 50/50, or less, as to whether they’ll agree to grow where you intend. My cacti, it turns out, are some of the most cooperative, easy to propagate, fast growing, and fascinating plants in my baby gardens. Ultimately, I’m envisioning a mosaic of tightly clustered cacti mounds full of texture and form. That will take a minute, but in the meantime, I’ve also found some good companion plants that can help build out texture, cover soil, and provide a little dappled shade relief from the blazing sun (cacti can benefit from a little shade too). Indian rice grass is fantastic for this. It just shows up, basically. That, and an annual buckwheat that reseeds every year —a little fuzzy silver rosette that will eventually form a delicate umbrella of flowers. It’s an odd plant - best ‘en-masse’ as they say, and looks like baby’s breath. I know that many New Mexico gardeners are learning what it means to grow plants in increasingly extreme conditions, with tighter limits on time and water. Many are also becoming more interested in ecological gardening. According to AI, ‘natural gardening’ is now the most common garden topic on the internet as people are actively seeking ideas and inspiration. So, I’d like to revisit something beautiful: the vivid, if fleeting, sequence of cactus blooms that unfolded this spring in Abiquiú over a period of six weeks. It’s hardly a comprehensive list of the species growing here—or that could grow here. I’m just limited to showing plant photos that actually belong to me. Check out more at: https://www.americansouthwest.net/plants/cacti/new-mexico.html Maximalism is the second most explored garden topic. To me, maximalism is best exemplified by the art of Dr. Seuss. I think the current vibe on that is essentially the same thing - layered, bold, weird, and wonderful. Cacti fit right in to that trend as well. In first to last to bloom order: By Karima Alavi Those of us who visit Plaza Blanca, the famed rock formation on the property of Dar al Islam, are used to approaching Abiquiu on paved roads. The next step is to drive up a slightly bumpy dirt road to the Plaza Blanca parking lot, before walking down to the white sandstone cliffs eroded by storms, winds, and water, the same elements that slowly cut gashes through them. This site offers a quiet haven to hikers, artists, and those who seek respite from the stress of daily life. I, for one, have taken for granted the ease with which I can visit Plaza Blanca, especially after reading Maria Chabot’s exquisite description of her visits to the site with her friend, Georgia O’Keeffe. Chabot was a Texas-born writer, photographer, and advocate for indigenous rights. Her strong interest in preserving native arts led her to facilitate the development of Santa Fe’s Indian Market. With their shared interest in the arts, Maria and Georgia O’Keeffe quickly became close friends. Chabot assisted with the restoration of the Abiquiu home O’Keeffe purchased, noting the charming, but rustic condition of the property that was apparently inhabited by some very stubborn pigs. When in need of a break, when seeking the tranquility that nature offers, they jumped into Georgia’s Ford coupe and made their way, with absolutely no roads, up the arroyos toward the area they called the “White Place.” An arroyo is a natural channel, or wash, that is dry most of the year. The problem is that they can turn treacherous in minutes by filling with water, rocks, and branches that tumble down a mountain at a dangerous speed. For this reason, O’Keeffe and Chabot knew exactly what to watch out for—clouds. Those simple, white, innocent looking clouds that could signal a warning that you’re driving your Ford straight toward a flash flood.

Through her many paintings of the “White Place,” O’Keeffe has made people aware of this natural treasure, a hidden gem, situated on the land owned by Dar al Islam. (See information below if you wish to visit the site.) The teachings and spiritual practice of Islam emphasize the concept of Environmental Stewardship, emphasizing the religious obligation of Muslims to be stewards of the earth. It is incumbent upon Muslims to protect natural resources which, as part of God’s creation, are considered a sacred gift. Islam’s religious text, the Qur’an, encourages humans to be humble toward the earth: “The true servants of the Most Compassionate are those who walk on the earth humbly” (25:63). Scholars point out that this verse encourages us to do the least damage while on the earth, and to protect the environment for future generations rather than just thinking of ourselves. Environmental activism in an Islamic context also unites the concept of justice with that of generosity. Chapter 54, verse 28, of the Qur’an makes it clear that resources are to be shared equally, even if one person (or tribe) has received more abundance than others: “And let them know that the water is to be divided between them, with each share of water equitably apportioned.” In this way, people maintain a sense of justice, while avoiding greed or wastefulness. Though little is known today about native settlements in Plaza Blanca, hikers have encountered subtle indications that people have inhabited the area for centuries. It is known, however, that this area has always been considered sacred by the many native tribes that had a presence in the region, including Hopi, Tewa, Apache, Comanche, and Navajo. The area often resonates with an air of sanctity, and if one looks closely, they can still find subtle outlines of ancient structures, or perhaps early gardens, made of rocks that are slowly sinking, disappearing back into the welcoming earth. Recently there has been an increase in connections between Dar al Islam, the O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, and the Abiquiu O’Keeffe Welcome Center. My January 17 Abiquiu News article told of Dar al Islam’s application for a Trail Mapping Grant. Letters of support from both the museum and the welcome center were instrumental in Dar al Islam’s receipt of a $100K grant. Visitors to Santa Fe’s O’Keeffe Museum and the Welcome Center have enjoyed tacking on an additional excursion to their tours. On May 12, 30 people from the museum toured the mosque, education center, and its surrounding property after enjoying their visit to O’Keeffe’s home. In April, another group of 13 visitors added a trip to Dar al Islam to their itinerary. There are also random O’Keeffe visitors who make their way up the road on their own, as happened last Friday when I exited the mosque from joining the Friday prayers and encountered a woman from Georgia. She told me that someone from the O’Keeffe Welcome Center had suggested she make the short drive to the mosque. She also spoke of the sense of tranquility she sensed upon entering the building. Georgia O’Keeffe herself visited Dar al Islam. She arrived in the early 1980’s after construction of the mosque was completed and the educational facility, connected to the mosque, was being built. According to Walter Declerck who encountered her on the site, it was the many arches moving down the central hallway that intrigued her the most.

Just watch out for those gentle puffy clouds O’Keeffe loved to paint. They can be tricky. "A Celebration" by Georgia O'Keeffe (above) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Celebration_1924_O%27Keeffe.jpg To read more of the excerpt from Chabot’s writings on Plaza Blanca, go to: https://www.zibbywilder.com/post/2018/12/01/plaza-blanca-georgia-okeeffes-white-place

So screwed. By Zach Hively Sometimes, we experience moments of wonder that modern science cannot explain. Yeah, yeah, we now live in an age of magic because modern science has been defunded. But these moments are no less special for not being peer-reviewed. Truly spiritual glimpses beyond the veil of reason have no equal in this life, except maybe ice cream. I experienced the inexplicable just this Sunday. So there’s this door that just keeps coming loose. I’m not a big-time door person, by any means, so I don’t know how to explain it more technically than that. The door comes loose, and it always has, ever since the beginning of time or ever since the previous tenant, whichever came later. Every now and again the door gets looser, and my beloved asks me to tighten it—not because I am a man and thus more competent, but because I am taller and thus more competent. I find a screwdriver—seldom the same screwdriver, and seldom in the same drawer—and I righty-tighty whatever screws still remain. The door closes a little more easily, for a time. A little less like there’s a foot or some small child in the way. A week later, or a day, the door loosens right back up. It’s like the old cross-stitch saying: When God closes a door, He has to lift up on the handle and put His shoulder into it.It’s the only way He can be sure to keep the cats out of the garage. As I said, the door has been this way forever. Which makes what happened next all the more inexplicable. The door came loose. Really loose this time. Loose enough to frustrate whatever Almighty is out there. I was not surprised, seeing as all the screws in all the hinges only I can reach still went righty but had ceased going tighty. My beloved asked me to fix it again. Only this time, unlike all the times before … I KNEW HOW TO FIX IT BUT FOR REAL. “Do we have toothpicks?” I asked. We did. “Do we have wood glue?” I asked. We did. “Is it hanging out with one of the screwdrivers?” I asked. It was. “Do we have any idea where I learned this?” I asked. We did not. You cannot science me into understanding how, exactly, I knew the tried-and-plausibly-true method for fixing stripped screw holes with quite literally the smallest pieces of lumber available on the market today. I—and I cannot stress this enough—am not handy. I tend to fix things by ignoring them until they go away. I have removed doors and lived without them rather than repair them. This toothpick trick is not something I could possibly know. If trauma can be inherited through DNA, can handiness be passed on, too? This toothpick-fix feels like something Papaw would have known. It’s entirely possible my parents knew this fix too—it would explain the box of toothpicks from my childhood that’s still around here somewhere—but that I was too busy re-reading Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew books to pay attention to the home repair tips that, until Sunday, were not relevant to me. Yet wherever I absorbed this knowledge, I mustered the undeserved confidence that only every man on the planet can muster. I coated those toothpicks in wood glue. I stuffed them into the screw holes. My beloved fed me salami and licorice and told me I was sexy. I got door hinge grease on one of my fingers. We took a nap that I got to count as “curing time.” Then came the moment of truth: Screwable, or screwed up? I am thrilled to report, with no spin whatsoever, that my unearned knowledge worked on all but one remaining screw. Which I am obligated to point out is on the bottommost hinge, where my beloved can reach it. Her problem now.

The door closes with silky ease. If it ever comes loose again, it might be time to sell the house and move to Europe. Or to try it again with multicolored toothpicks. Either way, neither God nor science can describe that high of repairing a door with no knowledge or ability whatsoever. It was the fourth-best feeling of my day. The third-best was that nap. The second-best was the chocolate chip cookie dough ice cream my beloved bought me as thanks. The first-best was sharing it with her. There’s no magical moment quite like an impromptu date. Just to be sure we didn’t ruin the moment, we left the house out the other door. SANTA FE – The New Mexico Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program returns Tuesday, July 1, providing nutritious, locally-grown foods to income-based eligible seniors, Native American elders and WIC families.

WIC Families must be actively enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Participants should contact their local WIC clinic to check their eligibility and access benefits. “This program gives people access to healthy, fresh local fruits, vegetables, herbs and honey in their communities,” said Veronica Griego, New Mexico Farmers’ Market Program Manager, which oversees the multiple programs covering all ages. “Healthy food makes for a healthier life and helps stretch food budgets at a time when every little bit helps.” The program also extends to seniors—residents aged 60 and older, and Native American elders aged 55 and up—who are eligible to apply. An online application is available at www.nmwic.org/fmnp. Paper applications are also available at New Mexico Department of Health public health WIC offices, senior centers, as well as the Area Agency on Aging and the AARP, the American Association Retired Persons. “As the cost of food continues to rise, these additional funds for fresh produce make a difference for participants in need by providing them with more essential nutrients,” said Sarah Flores-Sievers, New Mexico WIC and Farmers’ Market Director. Eligibility is determined by household size and income. Those who’ve applied in the past must reapply to verify eligibility. Benefits are limited and distributed on a first-come, first-served basis. Seniors and Tribal elders already enrolled in the program will be able to start spending their $50 in food funds July 1 at any one of the dozens of participating farmers’ markets, mobile markets or roadside stands statewide by using their shopper cards or smartphone apps. For more information and to find farmers’ market locations in your area visit www.nmwic.org/fmnp. ### NMHealth David Barre, Communications Coordinator | [email protected] | (505) 699-9237 NMHealth works to promote health and wellness, improve health outcomes, and deliver services to all New Mexicans. As New Mexico’s largest state agency, DOH offers public health services in all 33 counties and collaborates with 24 Native American Tribes, Pueblos and Nations. Republican-backed proposals to sell swaths of public lands represent an assault to tribal sovereignty, outdoor recreation, critical wildlife habitat and “our children’s birthrights,” U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-NM) said Wednesday. “In one fell swoop, these proposals threaten every form of outdoor recreation, every form of natural and cultural heritage and habitat for wildlife — all to pay for a tax handout,” Heinrich said during a discussion he hosted in Washington, D.C. that included other Democratic US senators, alongside hunters, wildlife advocates and legal experts. “That doesn’t sound very American to me, and it clearly doesn’t sound very American to the hundreds of thousands of people across the political spectrum in the West raising their voices right now.” Heinrich’s event comes as uncertainty prevails regarding a controversial proposal to sell off public lands to build housing spearheaded by Republican Sen. Mike Lee from Utah. After the U.S. Senate Parliamentarian determined earlier this week that the language in Lee’s proposal did not comply with the Senate’s rules for budget reconciliation, Lee said he would revise the proposal and that he would exclude U.S. Forest Service land and limit the Bureau of Land Management land to areas near “population centers.” Heinrich, the ranking member of the Senate’s Energy and Natural Resources Committee, applauded the parliamentarian’s decision, but warned “the fight is not over.” He pointed out the finality of selling off public lands, saying: “Once these lands go into private hands, we will not get them back. From the date of sale, the land must be used for what it is sold for: development. It can never be used for conservation, recreation, hunting, fishing — all the things that these lands provide today.” Hilary Tompkins, a former solicitor in the U.S. Department of the Interior in the Obama administration, said Lee’s proposal bypassed tribal consultation, even though much of the land in question lies in Indian Country.

“There’s also no clear protection for sacred sites and cultural resources of tribes and the public lands that would be sold to the highest bidder,” Tompkins said. She noted the original proposal identified U.S. Forest Service lands on Mount Taylor in Grants, New Mexico, one of four mountains sacred to the Navajo nation. “This is a very precious place for me and my family, and we have conducted important ceremonial life journey milestones involving that mountain. We cannot put these precious places on the auction block,” said Tompkins, who is originally from Ramah, New Mexico. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nevada) urged Lee to listen to people with concerns about sales of public lands. “If he wants to do something in his own state of Utah, more power to you, go do it, work with all the stakeholders, let’s do it,” she said. “But don’t come into our states and dictate what should be done.” Heinrich pointed to his recent experiences fishing on Pecos River, and said while the lands are some of his favorite places in New Mexico, it’s crucial that they remain open for future generations. “Public lands are an essential democratic part of American culture and identity, and they belong to us,” he said. “They define us.” |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed