|

Flows in the Rio Grande at the Otowi Bridge are at 34% of the historical median for this time of year and water levels in Elephant Butte Reservoir are declining as irrigation season gets underway, according to information presented to the Interstate Stream Commission this month.

Deputy State Engineer Tanya Trujillo said “significant efforts” are underway to administer water on the Rio Grande during the dry times. “We’ve seen some benefits from rain in these past several weeks, but we know that the conditions are going to be very critical and difficult to manage in the coming summer months,” she said. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham declared a state of emergency due to drought conditions in late May. As of June 10, Elephant Butte reservoir was approximately 10% full. Some of the models that water managers rely upon indicate that the reservoir levels could drop below 30,000 acre-feet before the end of July. Those low levels haven’t been seen since the 1950s when there was a severe drought in New Mexico. New Mexico continues to face restrictions under Article VII of the Rio Grande Compact, which means the state can’t increase its storage in reservoirs that were built after 1929. The only native Rio Grande water — meaning water that isn’t brought in from other basins — that is being placed in storage is the prior and paramount water, which belongs to the Pueblos. Interstate Stream Commission Hydrologist Grace Haggerty said the agency’s Rio Grande Bureau “has been responding to a deepening compact deficit by evaluating causes and formulating potential solutions with the state engineer’s office.” She said continued work to reduce New Mexico’s Rio Grande Compact debit — which occurs when the state delivers less water than required — “is critical for all users along the Rio Grande, especially as model predictions are showing 25% less water…in our rivers in the foreseeable future.”

0 Comments

State lawmakers assess health rankings ahead of potential Medicaid cuts BY: AUSTIN FISHER Courtesy of Source NM Even though state lawmakers have allocated billions of dollars in the last few years to improve access to health care, New Mexicans’ physical and mental health outcomes have remained the same or worsened, health officials and legislative analysts say.

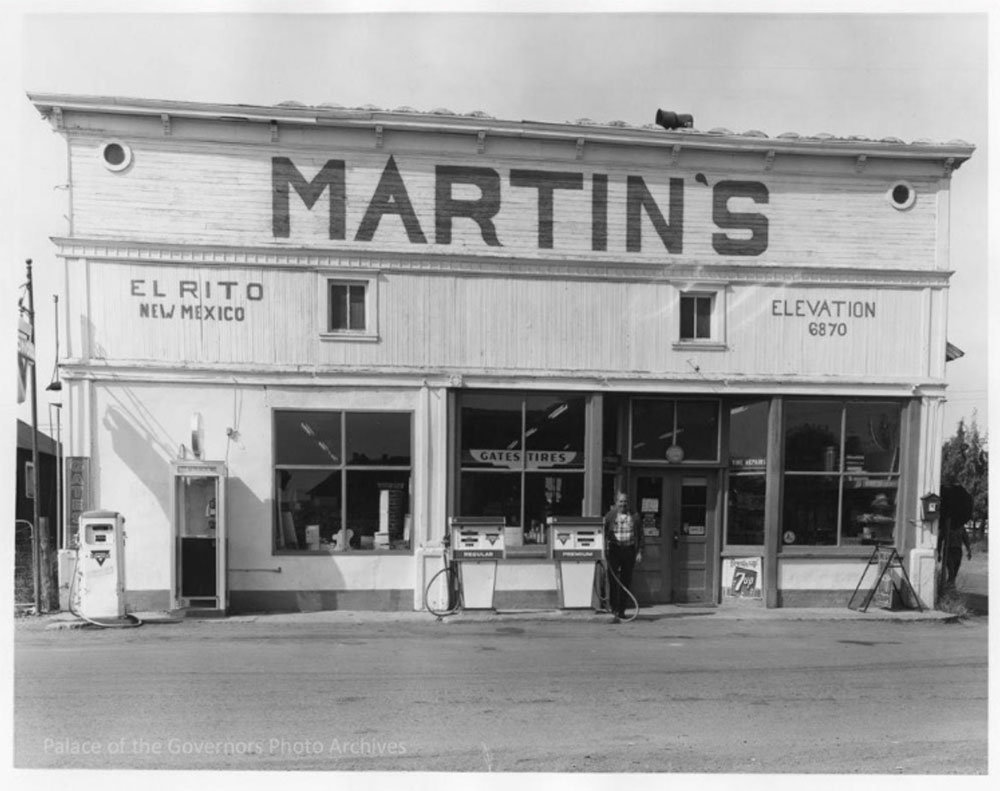

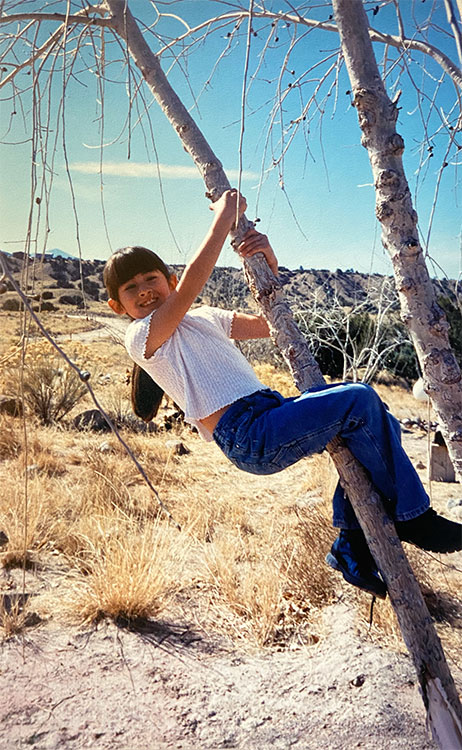

A higher proportion of New Mexicans of all ages had substance use disorders in 2024 compared to the prior year, and more young people had major depressive episodes, according to data cited in a presentation by Legislative Finance Committee Analyst Eric Chenier and New Mexico Health Care Authority Secretary Kari Armijo. While fewer women in New Mexico are dying during or shortly after pregnancy, more children are being born with low birth weights and withdrawal symptoms from being exposed to drugs while in the womb, according to data cited in the presentation. As for access, fewer people are actually going to doctors’ offices than before the COVID-19 pandemic, but more people are seeing mental health practitioners, the data show. The report notes that it relies on utilization data that only shows if providers billed for more services, not necessarily if more Medicaid patients are receiving care. New Mexico ranks 16th in access to behavioral health care overall, Armijo told the Legislative Finance Committee at its meeting in Taos on Wednesday. “We’re not at the top, but it shows the interventions are working,” she said. “The state has really done a lot of work to rebuild the behavioral health system. We’re struggling with a new set of issues, in many ways, that weren’t present a decade ago.” Medicaid The New Mexico Medicaid program operates as the largest payer of health insurance in the state, covering approximately a third of the state’s population, Armijo said. According to the presentation, Medicaid is “the greatest lever available to the state to reduce the prevalence of mental illness and substance use disorders and improve physical health for women and children.” Approximately 4,000 new health care providers have joined the Medicaid network in the last 11 months, Armijo said. Of those, 57% work as behavioral health providers and 29% are in primary care, she said. Lawmakers most recently increased provider reimbursement rates to 137% of the rate paid by Medicaid, Armijo said. New Mexico has paid out $2.2 billion in reimbursements to health care providers, Chenier said, including $1.3 billion to hospitals and $90 million to behavioral health providers. New Mexico has put approximately $550 million in one-time funding for behavioral health services, LFC Analyst Eric Chenier said. Armijo said the Medicaid unwinding at the end of the public health emergency for COVID-19 resulted in the number of people enrolled in the program to drop from more than 1 million to approximately 839,000. She said the rolls are “leveling off” and are not growing. Primary care Primary care is an entry point for behavioral health because it is the most likely setting where someone will actually receive behavioral health services, Armijo said. Primary care providers can prescribe medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorder, for example. Among all U.S. states, New Mexico ranks 29th in access for primary care services, according to data in the presentation. “It’s not where we want to be, but [it’s] not the worst,” Armijo said. The network of primary care providers has grown every year, Armijo said, and nearly every provider in the state received a raise because of lawmakers’ reimbursement rate increase that went into effect in January. For future discussions, Sen. Michael Padilla (D-Albuquerque) asked about a way to gather data on how long it takes for new patients to see a primary care provider versus existing patients, and how that breaks down between urban and rural parts of New Mexico. How the ‘one big beautiful bill’ could play out Because of Medicaid’s outsized influence in New Mexico’s health insurance market, the federal tax and spending legislation under consideration by Congress would impact not only Medicaid recipients but all New Mexicans, Armijo said. New Mexico would lose $2.8 billion in federal medicaid funding under the reconciliation bill, she said. The legislation would result in 111 health care providers losing funding, Armijo said, and the potential closure of between six and eight rural hospitals. Almost 90,000 people would lose Medicaid because of work requirements and other requirements proposed in the bill, she said. People on Medicaid are often working a minimum wage job, she said, while others are elderly or disabled who can’t just go out and find work. “When you have people who are working, and new work requirements, you have to be very careful about how you’re administering that: You don’t want people losing it because of administrative hassle,” Armijo said. “Work requirements can be confusing to comply with." Interview with Michael Martin, grandson of George Martin Senior By Jessica Rath Image credit: EatingAsia CC 2.0 How many of you, our esteemed readers, remember General Stores? Before supermarkets, shrink-wrapped groceries, packaged goods, self-checkout, credit cards, and so many more new-fangled contraptions? When sugar, flour, beans, etc. were stored in big bins and had to be hand-measured into a paper bag by a clerk who then weighed the item and calculated the cost? In Germany where I grew up, such stores were common at least until the end of the 1960s, even in big cities where one could find several supermarkets as well. Image credit: EatingAsia CC 2.0 Martin’s, the general store in El Rito which closed its doors for the last time on August 29, 2009, was different from my German memories. At Martin’s, besides groceries one could buy horseshoes, nails, screws, bolts, and hammers, pails, ropes, medicines, crockery and dishes, soap, lanterns, chicken feed, kitchen gadgets – just about anything the local families and farmers might need. Oh, and one could get gas, too. It was a sad event for the community when the store closed, people had to drive to Abiquiú or Espanola for almost everything. The building stood empty, but unchanged for many years. I always wanted to find out more about its past. Greg Martin, who ran the store until it closed and who is the grandson of the original owner George Martin, moved to Albuquerque, I learned. But his cousin Michael Martin (everybody knows him as Mike), who is the Chair of Northern New Mexico College’s Board of Regents, lives in El Rito and kindly agreed to meet with me. Over a cup of coffee at the Abiquiú Inn we had a lovely chat. First of all, a quick family history, so you’ll know who Mike is referring to later. George Martin Senior started the store together with his business partner John Sargent in the 1920s and eventually became the sole proprietor. He was married to Margaret Allen Martin, an Irish nurse with the nickname Dambo, who ran a Maternal and Child Health Care Center in El Rito. They had five children: John, Tom, Roberta, George and Pat. Tom, and later Tom’s son Greg ran the store until it closed. “The Martins also acquired a ranch, later managed by their son Pat, daughter-in-law JoAnn, and grandchildren Mike and Tim.”(1) Which means that Mike, the person I was talking with, is the grandson of the store’s original owner, and that his uncle Tom and later his cousin Greg ran the store, while he grew up on his father’s ranch. Where did your family originally come from, I asked Mike. “My grandfather, George Martin, came from Alsace Lorraine, and went to school at Manhattan University in New York,” I learned. “Then they thought he had tuberculosis, so he came out west for his health. Because he had a bachelor's degree from Manhattan College, and they needed somebody to be the principal at the school here, he moved to El Rito. And then he met my grandmother, who was originally from Ireland, Margaret Allen, and they were married in 1912.” Wait a minute – is Mike talking about the El Rito campus of Northern New Mexico College? I had no idea it had such a long history. (1)Rio Grande Sun, Obituaries Image credit: Gia Marie Hook “It was founded in 1909 as a normal school to train teachers”, Mike informed me. “It actually became a college before we were even a state, in 1912.” This is so interesting that I had to do a bit of research. The school was known as the Spanish American Normal School and was a teacher training institution, originally meant to train students to become teachers for the local schools in Northern New Mexico. It was the first institution for Hispanics in the United States. In 1969 the last class graduated from Normal School, and it became part of Espanola’s Northern New Mexico College in 1971 (actually, a community college until 2005). Image credit: EatingAsia CC 2.0 “My grandfather was working at the college,” Mike continued. “He was their first principal in 1910, and then in 1913 they promoted him to be President. He was president for one year, because in 1914 they moved the family to Pueblo, Colorado. They moved back to El Rito in 1925, and George went into partnership with a man by the name of John Sergeant. They both had a store together. Eventually the partnership dissolved, and my grandfather went into business by himself. This must have been about 1930, where the current Martin store is.” “My grandfather's degree was in languages. He spoke German, French, English, and Spanish. He was very good friends with Mr. Bode, with Martin Bode, Karl's father.” Sure, because Martin Bode immigrated from Germany at the turn of the last century. The area of Alsace-Lorraine was part of Imperial Germany from 1871 until the Treaty of Versailles at the End of World War I, and even today people in the region speak a dialect which is similar to Swiss German. At the same time, people are fluent in French and German. One can imagine that Martin Bode and George Martin would easily communicate in German. How was it growing up in El Rito as a kid, I wanted to know. Did you go to school somewhere in El Rito? Was there a school? I had no idea, of course. Mike corrected me. “I went to school here in Abiquiú, to the St. Thomas Catholic school. I started in 1964 in the first grade, and went through the spring of 1971 when they closed the school. That’s when I was in the seventh grade. I spent my eighth grade at El Rito Elementary, then went to Mesa Vista High School, and graduated in 1976.” So how did you get from El Rito to Abiquiú, I asked. “There were three or four families that carpooled,” I learned. “At the school, we had four nuns, and there were two classes for each nun, and school was held in what's now the Parish Hall. There were two classes in each room per nun.” So there was no school bus, I wanted to confirm. “Well, there was a school bus that picked up the kids here in Abiquiú, but it didn't go all the way to El Rito,” Mike explained. When I heard that Mike attended Mesa Vista High School near Ojo Caliente, I was reminded of my recent interview with Quentin Wilson; both he and his wife Maria had been teachers at Mesa Vista. Did he know them, was he their student, I asked Mike. “I know them both very well,” was his reply, but they were not his teachers. “He is quite the adobe specialist, and he helped us with some projects at our house.” Funny, how this all weaves together. But then again, in small towns everybody knows everybody, of course. Mike went to college at the New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, and graduated in 1980 with a bachelor's degree in agriculture and economics. And then he returned to El Rito and worked on the ranch, because his father inherited the ranch, while his Uncle Tom got the store. I imagined that it would be fun for a young kid to spend time at a grocery store where everybody you know would show up sooner or later. But it turned out that I was wrong. “We used to help my Uncle Tom do the inventory at the end of the year”, I learned, “but that was about the extent of my time at the store. We stayed pretty busy on the ranch with all the work to be done there.” Sure, that made sense; I didn’t think of that. But I did want to hear about the store – was it a true general shopping place, where one could purchase just about anything, I wanted to know. “Yes, it was a general store,” he confirmed. “They had everything. They had groceries, they had hardware, dry goods, just about anything that you need. My Uncle Tom had horse shoes, plumbing parts, feed for the livestock, candy, and he had a gas station as well.” Image credit: EatingAsia CC 2.0 “The store was really busy for a long time. My uncle used to have a couple of gentlemen working for him, and then a couple of young boys would come in after school and help them with stocking the shelves. Yes, they did a lot of business.” As Mike was talking, I could almost picture everything, the cash register, the balance scales to weigh dry goods, the baskets with apples, carrots, and other produce. I could smell a mixture of onions, garlic, and spices. “When they first had the store, there was a big counter in the front. You came in and gave your list to the proprietor, and they filled your order while you waited for your items. Then later they switched over to where you would actually go shop for yourself. But for a long time, there wasn't anything like self serving. No, you came in and visited with the other people while they got your groceries together.” It must have been a social hub of sorts, where people could meet and hang out. Mike confirmed: “The post office was right across the street; the building that’s right next to El Farolito used to be the old post office. So, everything was right there together. You could come to get your mail and then you could shop. And you could get the gasoline for your tractor or your truck.” And then it all changed. It became harder and harder to make a profit because customers dwindled. Were there more people living in El Rito then, or why did business sort of peter out? “I think people weren't nearly as mobile back then as they are now,” Mike explained. “And they couldn't easily get to town. You know, back in the 20s, there were very few automobiles in El Rito. People just had horses and teams and wagons, and it was just subsistence living. It was a big deal to go to Espanola even back in the 60s.” And there were no streets, only dirt roads. If it was raining, it would be a drag to go to a store somewhere farther away.But then your cousin Greg at some point had enough, I suggested. “Yes, Greg closed the store in 2009. He had run it since 1974 or so, and business had slowed down. A lot. People were doing a lot more shopping in town, and he was just ready for some peace and quiet.” Was it sad and difficult for the community when the store closed, I asked Mike.

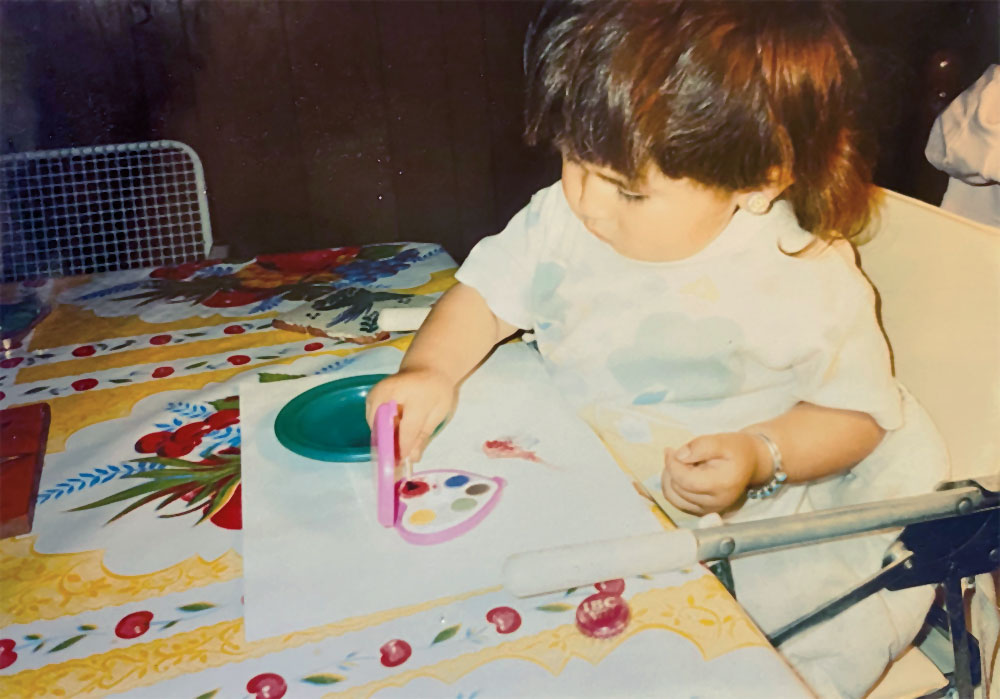

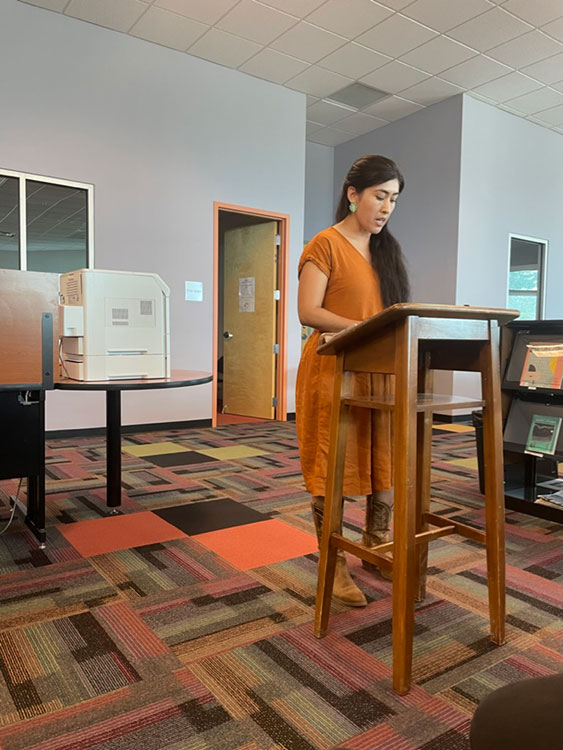

“Yes, it was very hard,” he confirmed. “Greg was the only one selling gasoline fuel at that point. The other store in El Rito had been selling fuel, but then they stopped so we no longer had any gas station in town. We had to drive to Bode’s or go to Espanola or to Ojo Caliente to get fuel, and that was a big adjustment for everybody.” I asked Mike about the work on their ranch, what he had to do when growing up. “We had a lot of cattle,” he told me, “so we had to irrigate some fields and grow alfalfa, and then we cut it and made hay bales. We’d take the cattle up into the mountains, to our forest service permit area, and they'd spend the summer up there. So we had to go up there and check on them, and then we’d bring them back home, so they'd spend the winter there in El Rito on the fields, and we'd have to feed them every day. Taking care of animals was a big part of the routine.” Mike had a final word: “The community has been very, very good to our family. They were always supportive and I've always felt lucky. It’s been a privilege to be able to live in El Rito.” Thank you, Mike, for telling me about your family, about your past, and about the iconic store in El Rito. Interview with Santana Shorty By Jessica Rath What better way to introduce a poet and writer than with one of her poems? So, here it is: Lake Valley At the end of the road, there is a gate It is an old gate The kind that takes two arms to pull Common rez courtesy means the passenger opens the gate while the driver passes through The mud ruts make everything hard An abandoned one room house keeps guard at the gate Someone told me once a family of five lived there I don’t know if it’s true, but it could be There is a thrum in the ground Petrified wood scatters with pottery shards The wind carries small porous pebbles of ancient lava In the distance, I see a group of wild horses The days of taming them are gone The road has alternate paths forward A way cut through when the rains came At the end of the road is the house, hogan, and corral A lonely tornado ruined the house long ago someone told me Many people once came here for ceremony My grandfather sat at the head of the hogan A circle of us sat along the wall Tobacco smoke holding the room, keeping us warm There was blue corn mush and elk meat with piñon There was tea in a pail There was sweet corn and canned fruit I used to pick out the cherries for myself The thrum tenderized the ground The drum pulled the room inward to the fireplace A song carried out the chimney, ribboned with wind that finds me here today, years later opening a gate for ghosts to pass through Santana Shorty A good poem captures your attention by building a multi-dimensional picture: it creates a rhythmic, visual image which is imbued with your feelings, memories, and thoughts, as if tiny hooks would pull little snippets from your mind and weave them into a reflection of the words you read. At least, that’s my experience reading Santana’s poem, and now I want to learn more. When did she start writing poetry, how did she become a writer? Although she has a full schedule, Santana graciously agreed to chat with me. She was born in Santa Fe and grew up in Abiquiú, Santana told me. The family lived in Plaza Blanca, and when she was about eight years old her parents separated. She and her Mom moved to Barranco while her Dad moved to Lindrith, a small village past Coyote and Gallina. Santana’s father is Navajo, and she is a member of the Navajo Nation. Her mother is Anglo and has been a teacher at Abiquiú Elementary for many years. Santana started school there, then went to Fairview Elementary in Espanola for a couple of years because her mother was teaching there, and then returned to Abiquiú for fifth and sixth grade, again because her mother was teaching there. For middle- and high school she attended the Santa Fe Indian School in Santa Fe. “My mother is an amazing teacher,” Santana told me. “She's taught for 25 years, and she always stuck with elementary, first grade, second grade, those are her favorites. She encouraged my and my sister's artistic interests, she really nourished those. I've always been a big reader, and she got me the books I wanted to read. So I've been reading a lot ever since I was really young, and I've been writing since I was really young. My Mom did a remodel recently and found a bunch of boxes filled with things that she had collected over the years. In some of the boxes there were some journals with poetry I wrote when I was six years old.” How nice of her mother to preserve all these early records! I bet it was fun to sort through them. For middle- and highschool, Santana was a dorm student at the Santa Fe Indian School, something that was both challenging and enriching. On the one hand, it was hard because she loved Abiquiú and being with her family. She would try to spend the weekends at home, but often Cross Country and Track and Field events took place on Saturdays. It was inconvenient to go home for one night and be back at the school by Sunday afternoon, so she would stay for close to two weeks sometimes. On the other hand, it taught her self-reliance and independence. “I was valedictorian of my school, and I got a full-ride scholarship to go to Stanford, which is where I went for my undergraduate studies,” Santana explained. “One of my main extracurriculars was poetry.” I wanted to hear more about Santana’s poetry. She had mentioned that she wrote poems at an early age – what motivated her? Is it even possible to put that impulse into words? She had to think about this for a moment. “For me, it is a way of processing the world,” she answered. “The artistic component is a byproduct of trying to understand life and experiences. It's not always that I want to write a good poem. It's that I have something on my mind that I can't let go of. The only way for me to satisfactorily explore that is via poetry. And then afterwards I recognize that I have a piece here that I want to work with.” This is so interesting. It’s almost as if something is nagging her, as if a poem knocks on her head and wants to come in and then she has to explore the meaning of it. Santana explained further: “A lot of artists have their little obsessions, the things that they have to return to again and again, and maybe at some point they can move on to the next thing. It's part of that. You have to get it out of your system, you have to explore this thing so many times, until you can finally put it to rest and don’t have to think about it anymore.” And what are the things that want to be explored, I wanted to know. Do they come from the past? Or from relationships? Do they come from nature? “For me, what tends to be knocking usually comes from nature,” I learned. “I write a lot of poetry about landscape, and the desert. New Mexico. That's something I can always write about, and will forever be obsessed with. Sometimes it also can be current events or a life experience.” She continued telling me about her education: “I went to Stanford in the Bay Area, and I graduated with a biology degree. I didn't really know what I wanted to do, so I ended up in the tech industry, and I worked in the tech industry for a long time in the Bay Area. In 2019 I moved back to New Mexico because I missed it and I wasn't really happy in the Bay Area anymore. I tried to pivot into a career in the public sector and I worked for the Santa Fe Public School District in their Native American Student Services Program. I was hoping to shift into a full time government position, but then the pandemic hit, and there was a hiring freeze. So I went back to the tech sector because it was reliable.” “I was working for a bank creating banking software,” Santana continued. “During all this time I was writing. I wanted to get more experience with writing, I wanted to learn how to write more formally. So I started to take some continuing education classes with UNM and the Institute of American Indian Arts, and eventually one of the teachers encouraged me to apply for the IAIA’s MFA program in creative writing. But I didn't know if I was good enough, I didn't know if I had the credentials. My Dad also went to IAIA in the 80s for Studio Arts. He's a sculptor and a painter. And so eventually one of my poetry teachers from the Continuing Ed classes pushed me a little: ‘Come on, you should have already applied!’ So I did, was accepted, and started the program in 2022.” It was fascinating to listen to Santana. “It was the best decision of my life, I found my people and my community in that cohort. I had started a novel, and the program helped me finish the novel, I finished the first draft in February of last year, and I graduated in May. After getting my MFA I really wanted to have my writing passion mimic my day-to-day existence. It felt as if I had split personalities, my big-girl banking job in the daytime, and then writing at night. What job could I do that would enable me to do both?” “And then two weeks after my graduation the president of NMSA (New Mexico School for the Arts) here in Santa Fe called me and said that they had an opening for the Creative Writing Department chair position! I applied, started the interview process, and they offered me the job at the end of June last year. So I gave notice to my banking job, moved to Santa Fe, and started as the department chair. Now I teach creative writing to high school students, run the department, and I still get to work on my own creative projects and writing. Life has really shifted in the last year to align with my ultimate dream job.” Doesn’t this sound fantastic? We often have to work jobs simply to make money, jobs that are not ideal. But Santana could give up her banking job and now pursue her passion. She can work in a field that is most dear to her heart and that supports her. That's so impressive. Santana agreed. “For a long time, I didn't think of it seriously. I just thought of writing as my hobby. For many years, especially after graduating college, I didn't know what my dream job would be. I knew what my dream or my passion was, but to turn this into a job that would support me? I didn’t think that was possible. But I tried new things and pushed myself out of my comfort zone, and that’s how I found out what my dream job could be. Yes, I'm going to take a big pay cut from the fancy tech job, but I'm going to be so much happier.” What are some other goals, I asked her. “My short term goals: over the next five years, I want to grow this department and bring it to the next level. During my first year I made a lot of changes, and I'm excited that I have the experience now to improve even further. And I'd really like to finish revising the novel I've been revising since last summer. Starting a new job takes a lot of energy, and I had less time to dedicate to the novel during this school year. I want to find a better balance with that for the next school year. Revise the novel and find a literary agent who is aligned with me and my writing values. And eventually get the novel published. Plus, I have a lot of poetry that I'd like to compile and edit into a collection.” “And I want to do smaller writing projects along the way,” Santana went on. “I have an essay that'll be coming out shortly with resilience magazine, it’s a creative non-fiction essay. I’d like to take on some journalism projects. I'd love to apply for artist residencies and make space for professional development in that area. And, personally, I love Santa Fe, I was born here. I went to middle school and high school here. I lived here for a little bit in 2019 before I moved to Albuquerque, and then came back last year. I'm excited to build my community here among my circle of friends.” “I want to buy a house, that's a dream I have. I'd love to have a place in Abiquiú, but it's gotten so expensive there. It’s sad that people who grew up there can't afford to live there. Santa Fe is also very expensive, but there may be more opportunities. I keep my hopes open and keep thinking good thoughts about it.” The revision process for Santana's current novel sounds very intense. She’s rewriting everything, a big task indeed. At the same time, she’s working on smaller projects, to keep her sanity, she said – essays, poems, maybe short stories. Actually, short stories are the hardest to write, she told me. One has to be very efficient and precise, and that is really challenging. After she got her Master's Degree, Santana did a residency, I read on Facebook. I wanted to hear more about this.

“I applied to the Aldo Leopold Writing Program early last year. They used to only have the Tres Piedras residency at Aldo Leopold's house, and last year was the first year that they added a second residency location which is in Lany in the Galisteo Basin. There was a casita there, donated by a wonderful woman who runs a Horse Sanctuary out there. Usually the Leopold residency program is offered to people into nature conservation, just like Leopold was. Non-fiction botanists, or people who are writing books about birds or land conservation. I applied although I’m a fiction writer, because my whole story takes place in New Mexico, and the landscape is a big central theme of the story. So I applied, but didn’t feel confident about it. And then I was the first fiction writer they selected! That was one month last year, in July, that I got to just work on the novel, which was really special. I had never done a residency before, and I loved being out there.” “You're really on your own out there, but I was, I am so lucky that the Institute of American Indian Arts program is so supportive, so loving. I still have great relationships with many of the teachers and can ask any of them for help. So I did reach out to some of them, asking, how do I make the most out of this time? And they gave me a lot of great advice.” I hope Santana will find a skilled and talented editor soon. I can’t wait to see her novel published. What a strong and powerful voice she has. I found a YouTube video from fifteen years ago, of Santana reciting one of her poems, which is deeply moving in the current political climate when children are snatched out of schools and babies are torn from their mothers. With poignant opinions such as Santana’s, maybe all is not lost… Thank you, Tana, for talking with me, so that our readers can learn about you, your poetry, your life. NWS: Extreme heat, fire danger for New Mexicans this week; monsoon relief likely on the way6/18/2025 High winds will crank up the heat across New Mexico on Tuesday, prompting major heat risk stretching from the Middle Rio Grande Valley in Albuquerque, through the Lower Rio Grande in Las Cruces. Risk from extreme temperatures will include parts of Socorro and the state’s southeastern region, as Roswell is expected to reach 110 degrees. The winds will make that heat index, or “feels like temperature,” even hotter, said Michael Anand, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service office in Albuquerque.

“We have high confidence that we’ll see temperatures around 110 degrees in Roswell…hence why we upgraded that heat watch to a warning,” Anand said. Last week, the heat levels prompted warnings from NM health officials and raised concerns for nonprofits and providers serving people experiencing homelessness. The reality is that heat doesn’t have to reach triple-digits to pose dangers to people’s health, said Chelsea Eastman Langer, who leads NMDOH’s Environmental Health Epidemiology Bureau, in an interview last week with Source NM. She pointed to New Mexico Department of Health data showing that emergency room visits jump when the temperatures outside rise above 90 degrees, but that may not match up with expectations. “If it’s 90 degrees, people say ‘it’s not that hot, it gets worse,’” she said. “It is a challenge. And I would say it’s when we’re still kind of figuring out how to message and get the word out.” Langer said that health officials are working with employees at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on a proposal to lower the thresholds for issuing weather-related advisories below triple-digits. “What we see is that we start to get people coming in with heat-related illness at temperatures much lower than when they would issue [a warning],” she said. “We start to see people coming in to [emergency rooms] at 80 degrees and then there’s a pretty sharp increase at 90 degrees.” Dr. Emily Bartlett, an emergency physician in Gallup, said numerous groups of people face risk from heat: children; the elderly; people without home cooling equipment or shelter; outdoor employees; and anyone with health risks. “It’s not just the maximum heat, it’s the duration,” Bartlett told Source NM. “If it doesn’t cool off enough at night between days of high heat, it raises the risk of illness.” Bartlett said in hot weather, heat stroke, a potentially deadly condition which is usually exhibited by a fever of 104 degrees and neurological symptoms, represent the highest concern. “If someone is expressing altered mental status, acting confused, lethargic, not answering questions correctly — that should be presumed to be an emergency,” she said. “Just like with stroke or heart attack patients, we want to start early treatment, as well as getting that patient to a hospital.” Less serious conditions can include heat exhaustion and heat rash, which can be mitigated through cooling and hydration, Bartlett said. The winds also whip up fire danger concerns across the entire Western and Central portions of the state, as officials battle two southern New Mexico fires north of Silver City. Chances for the seasonal monsoon rains are increasing and may arrive as soon as the weekend, Anand said, offering chances of thunderstorms and rain for most of the state. “It’ll be hot and dry until the monsoon plume kicks in on Sunday and Monday of next week,” he said. The New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission will hear fiscal year 2026 priorities and work plans when it meets Wednesday in Albuquerque.

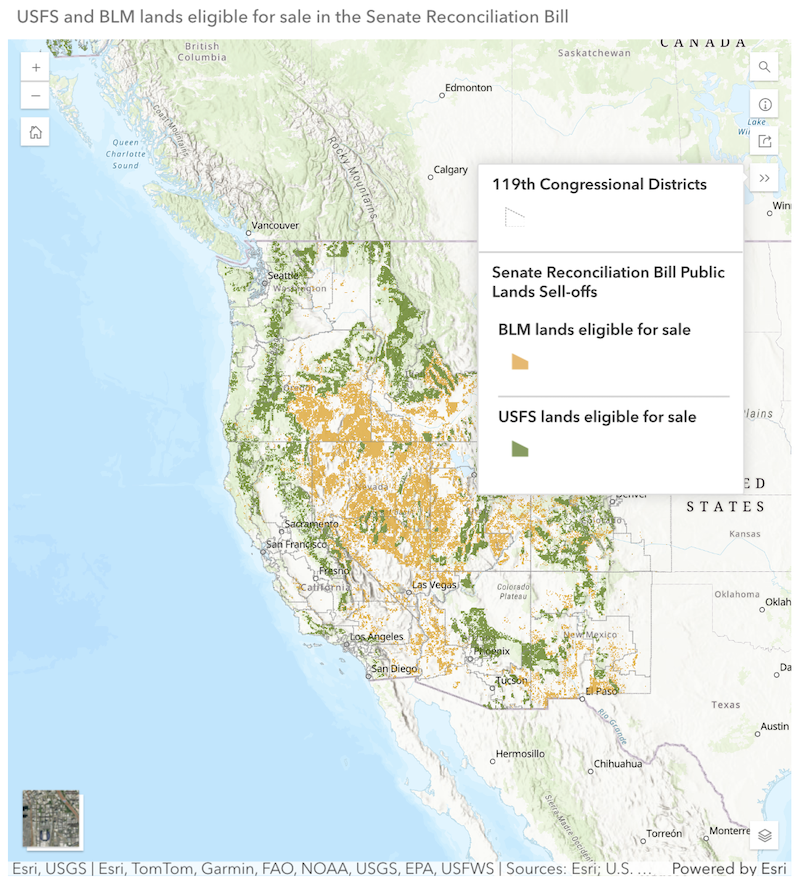

The commission will meet from 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. at the Office of the State Engineer/Interstate Stream Commission, 5550 San Antonio Dr. NE. The public can also join remotely. Information on how to remotely attend the meeting can be found here. The first hour of the meeting will be a closed session. The public can tune in for the open meeting starting at 9:30 a.m. During the open session, the staff will present work plans for fiscal year 2026, including details about how money will be spent in the Middle Rio Grande. Middle Rio Grande The Middle Rio Grande work plan includes a total budget of up to a little more than $8 million. Some of the elements of the Middle Rio Grande work plan include analyzing how evaporation impacts how much water is available and refining a water supply forecasting tool. The largest budget item for the Middle Rio Grande work plan is $3.4 million to support the strategic water reserve, which is a publicly-owned pool of water rights that helps New Mexico meet its compact obligations and comply with Endangered Species Act requirements. Earlier this year, the legislature passed a bill that added a third purpose to the reserve. That new purpose is to support aquifer recharge projects or to reduce groundwater depletion. The strategic water reserve is not to be confused with the strategic water supply, which is a recent effort to use treated brackish water and produced water — a byproduct of oil and gas extraction — to support industrial operations. The state may consider acquiring pre-1907 water rights to support the strategic water reserve, which could mean partnering with non-governmental organizations or other government agencies. Another $2 million could be spent on channel maintenance and restoration in the Middle Rio Grande. The work in the Middle Rio Grande basin — which includes the Albuquerque area — could also include endangered species work. The agency is looking at a budget of nearly $7 million to help endangered species that rely on the Rio Grande. The bulk of that money — $6 million — will be spent on habitat improvements and river restoration in the Middle Rio Grande. Some of the species that this funding will help support include the Rio Grande silvery minnow and the southwest willow flycatcher. Other work plans and projects Further south on the Rio Grande, the work plan for the Lower Rio Grande has a budget of up to $31.28 million. The biggest single budget item for the Lower Rio Grande is $10 million for stormwater capture and aquifer recharge. Another $7.5 million is budgeted for a short-term groundwater conservation program and $6 million is budgeted to identify, characterize, and quantify the brackish groundwater aquifers that could be used in desalination efforts. Albuquerque area residents may also be interested in the presentations on the Acequia and Community Ditch Infrastructure Fund Work Plan, which has a budget of about $5.58 million, and the Acequia Support Work Plan, which has a budget of up to $1.75 million. The Interstate Stream Commission will also hear the work plan for water planning initiatives, which is budgeted at around $7 million for fiscal year 2026. The commission previously discussed the Colorado River, Canadian River and Pecos River basins work plans during a May meeting. Other agenda items for Wednesday include agreements with the U.S. Geological Survey for river gaging statewide and the Mesilla Basin Groundwater and Surface Water Monitoring Program. The ISC is also scheduled to hear an informational presentation about aerial surveys in southern New Mexico that are part of an effort to characterize the aquifers in the Lower Rio Grande area as the state looks into possible supply augmentation. Closed session includes discussion of Texas v. New Mexico The meeting will start with a closed session to discuss the Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado case that is pending before the U.S. Supreme Court. In this case, Texas argued that groundwater pumping in New Mexico was impacting the amount of water Texas was receiving through the Rio Grande and thus violating an interstate compact. While it looked as if the case would go to trial this month, the United States government, as well as Texas, New Mexico and Colorado, requested that the trial be put on hold as they work on a possible settlement agreement. In addition to discussing the Texas v. New Mexico case, the closed session will also focus on the litigation on the Colorado River Basin. GOP bill makes 14 million acres of public land in NM ‘eligible’ for sale, according to new analysis6/18/2025  Highway 9, with federal grazing land on either side, in Southern New Mexico pictured in May 2025. The Senate reconciliation bill making progress this week makes more than 250 million acres “eligible” for private sell-offs, including federal grazing land, according to an analysis by the Wilderness Society. The bill mandates up to 3.2 million acres of public land be disposed of. (Photo by Patrick Lohmann / Source NM) The federal budget reconciliation bill making progress in the United States Senate this week makes more than 21,000 square miles of public land in New Mexico “eligible” to be sold to private buyers, according to the Wilderness Society. The group, which opposes efforts to sell off public lands, geographically analyzed lands across the West that could be subject to a land sale, based on criteria laid out in the bill. Across the West, several hundred million acres of land would meet the criteria, according to the group, though only a tiny fraction of that would be sold, per the bill text. The bill mandates the “disposal” of between .5% and .75% of all United States Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management land across the West, which means up to 3.2 million acres or 5,000 square miles. According to the Wilderness Society’s analysis, about 6.5 million acres of U.S. Forest Service land in New Mexico would be eligible, in addition to about 7.8 million acres of BLM land. According to a map the society created, huge swathes of BLM land east of Las Cruces also would be eligible, along with areas of the Gila National Forest and Santa Fe National Forest. This map visualizes the 250+ million acres of public lands eligible for sale in the Senate budget reconciliation package. Take action: Tell your senators to vote no on the reconciliation bill. Learn more about the bill and find the data here. Map and analysis by The Wilderness Society using source data from BLM, USFS, USGS, NPS, and SENR reconciliation bill text as of June 16th 2025.

The mandate does not apply to national parks, monuments or other “federally protected land” like historic sites, wildlife refuges or fish hatcheries. It also excludes land that is “subject to valid existing rights.” But it’s no longer clear what that last provision means, said Wilderness Society spokesperson Max Greenberg in an interview Tuesday with Source New Mexico. Until this weekend, “valid existing rights” applied to federal lands with grazing leases, but lawmakers struck the definition, according to Politico and leaked drafts the organization obtained. After lawmakers removed that definition, the Wilderness Society revised its estimate to 250 million acres of federal land eligible for sale, up from 120 million acres, Greenberg said. The figure reflects the sheer amount of federal land now leased for grazing across the West, he said, and also the secrecy in the legislative process. “This played out with kind of secret updates over the weekend and this very non-transparent, strange process where we have to work out what is actually implicated in the bill,” Greenberg told Source. “All of this argues for just [a] better process and better transparency… It’s been misleading the way the bill was initially framed by Republicans as this kind of very surgical effort to dispose of a few marginal parcels here and there.” U.S. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), chair of the Senate Natural Resources Committee, has said the mandated selloff would serve as a way to discard remote and difficult-to-manage public lands and turn them into housing developments. He made the pitch last week in a video he released, featuring Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Scott Turner. “Washington has proven time and again that it can’t manage this land. This bill puts it in better hands,” Lee said in the video. A previous version of the bill in the House contained about half a million acres of specific parcels of federal land to lose federal protections, but House lawmakers removed that language after pushback, including from U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez (D-NM). Vasquez called it a “huge victory” at the time. Emergency departments have reported increased cases of infants and young children coming in contact with substances like fentanyl, methamphetamine or even residue on household surfaces or drug paraphernalia. Some of these exposures have resulted in death. For curious toddlers, anything left within reach can be a danger.

Simple steps can help protect little ones:

If you suspect a child has been exposed, use naloxone — you can give naloxone to people of all ages — and call 911 immediately. Protecting children starts with supporting parents and caregivers. Compassionate care, harm reduction services and family-centered treatment options are available to help parents heal while keeping children safe. At Presbyterian Española Hospital, we provide confidential services including individual substance use disorder counseling, referral for medication management and connections to community resources for adults and adolescents (age 13 and up). If you or someone you know is struggling, call us on 505-367-0340. Am I just a late bloomer? By Zach Hively Oh, did I ever have grand aspirations. I am sitting outside right now, right where—starting six years ago—I imagined a modest if obscenely bountiful garden flourishing in this dry, inhospitable patch of sand. A lot of love and hard work, and as always some make-or-break luck, built this space into what I see before me today: A dry, inhospitable patch of sand. Which is not to say I have failed entirely as a gardener. Here, let me tally for you all the delicious things I have enjoyed—cumulatively, over these last six years—from lo these many efforts:

And all this—except the potato—came from container gardening. Which is still hard! I think the ground underneath the containers is a bad influence. Granted, I have had to deal with FACTORS. I’ve ranted before about the pack rats who chew anything that grows here down to the stubs. They make me think it was rabbits. Spoiler: it is never rabbits. Rabbits do not build modest yet obscenely bountiful nests in the engine compartment of my pickup truck. Nor do they festoon these nests with intact, uneaten garden stakes. (Alongside spine-in prickly pear pads.) Never mind the pack rats. And never mind that they intimidate me into pretending they don’t exist. I also have to contend with water. I grew up in one of those increasingly rare American cities with potable water straight from the tap. It was either entirely safe, or we didn’t know any better because of the silencing power of the local military-industrial complex. Either way! We all also watered our plants with it, and the plants generally survived. So I, privileged and oblivious, watered my first-year garden straight from the groundwater well. Not only was the water abundant, it was unmetered. It was also not discolored. But everything—and I mean everything, except the pack rats—died. Turns out, plants do not thrive on leaded groundwater. So I installed a couple rain barrels. You, astute reader, may see the fault in this plan faster than I did: Rain barrels require—and this is backed by empirical science—rain. Which we get! Sometimes! But do you know when plants least need watered? Right after it rains. Thus, I hoarded the water in those barrels, because watering my modest yet increasingly obscenity-generating garden used up their contents in about two goes. I drew out the supplies. Asked my lingering plants to go on austerity. (I had moved on from most delusions of edibility at this point. We were just holding out for some hardy flowers.) Ultimately I upgraded from the original two sixty-gallon barrels to an additional pair of 250-gallon beasts. One really good downpour fills them right up. Yet I, scarred and hardened now, as burned as my cat mint plants in July, still limped my plants along. I’m so averse to running out of water that I feel better when I leave the tanks full. All the while, nature taunts me: the wild datura that sprouted all on its own by the front door—and which I never once tended to—provides a full 96% of our annual flowerage, with blooms as big as my face. This year, I gave up. I didn’t plant a single seed. No trips to the nursery center. No starts, no plugs, no offshoots. I water the trees (which have not grown but also have not died) mainly when I remember to, which is seldom, because I have handed their fate over to Fate. Which means, of course, that the garden has picked up the slack. Every surviving sage plant has shot out new leaves after overwintering without a darn bit of assistance from moi. I have what I distinctly believe to be a fourth carrot growing. The containers are getting bushy with marigold greens and two rosemaries that just won’t quit. And then there’s these bad boys: Bad girls? Bad plants. Good plants? Whatever. These flowers did it all by themselves. I can’t even tell you when I last put hollyhock seeds in this trough or anywhere else. It was not in a recent year.

I think there are lessons to be learned here. Possibly about relinquishing control. Definitely about the transformative beauty of giving up. So remember, kids: If at first you don’t succeed, quit planting seeds. Don’t try so hard, or at all. And if you ever come over to see my flowers, best bring your own food. SANTA FE – No cost back-to-school vaccinations are available from dozens of medical providers statewide.

The annual Got Shots special immunization clinics will be held between June 14 – Aug 30 for all children 0-18 years-old. The New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH), the New Mexico Immunization Coalition, the New Mexico Primary Care Association, along with managed care partners Blue Cross and Blue Shield of New Mexico, Molina Healthcare, Presbyterian Healthcare Services and United Healthcare are making sure New Mexico’s children get their scheduled immunizations on schedule. "Vaccines are one of the greatest tools we have to protect children’s health. Safe and effective immunizations have dramatically reduced – and in some cases, eliminated – dangerous childhood diseases that once claimed thousands of young lives in the United States every year,” said Andrea Romero, NMDOH Immunization Program Manager. Participating providers – such as NMDOH public health offices - will offer immunizations to any child, regardless of whether they are a patient or have insurance, as part of Got Shots. Some providers hold clinics on weekends or evening hours to accommodate parents’ busy schedules. Parents should call ahead to the clinic to see if an appointment is needed. Parents need to bring their child’s shot record, and if they have insurance, their Medicaid or private health insurance card. Immunizations are provided at no cost to parents regardless of insurance. This year, 68 public health offices, community health centers, and private practices are participating in the Got Shots campaign. Click here to see the current School and Childcare Immunization Requirements. A map and list of additional statewide locations participating in Got Shots is available on the New Mexico Immunization Coalition page. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed