|

By Julia Goldberg

Source NM In a letter sent Tuesday to the acting secretary for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) and colleagues put forth a list of concerns related to wildfires, including a halt of fund disbursement for forest management and restoration projects, and what they characterized as a universal hiring freeze that includes permanent and seasonal firefighters. “As we have recently seen in Los Angeles, addressing the threat of wildfire — even in winter months —should remain a top priority for the Forest Service and the Department of Agriculture,” the letter to Gary Washington notes.“The funds provided by Congress for this work led to record-breaking accomplishments in forest management in 2024. Halting these payments is not only unlawful but also endangers our rural communities by removing a vital component of their economies and delaying critical work to mitigate the threat of wildfire.” The senators write that it is their understanding USDA stopped funding provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act or the Inflation Reduction Act in response to President Donald Trump’s executive order, and suspended hiring firefighters in response to Trump’s order to freeze federal hiring, even though his order exempted public safety personnel. A federal judge on Monday ordered the Trump administration to comply with the judge’s previous ruling requiring the government to unfreeze funding on grants and loans. The letter also includes 10 questions to the department, including a request for a full list of the Forest Service programs for which funding has been paused; the status for personnel hired under both the IIAJ and IRA; and an explanation for the hiring freeze for firefighters despite the public safety exemption. For their last question, the senators write: “In recent years, the Forest Service has spent months at a time at Preparedness Level 4 and 5, indicating that staffing levels were stretched to a breaking point. How does the Department plan to effectively fight wildfires if the Forest Service cannot hire firefighters?” In addition to Heinrich, who is the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, fellow committee member U.S. Sen. Patty Murray (D-W.A); Subcommittee on Interior, Environment Ranking Member U.S. Sen. Jeffrey A. Merkley (D-Ore) and Ranking Member Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Amy Klobucha (D-MN) signed the letter. Read the full letter here.

0 Comments

By: Patrick Lohmann Source NM Mayordomos and other acequia advocates from across New Mexico gathered at the Roundhouse on Tuesday, carrying shovels and signs calling on lawmakers to expand a recurring stream of funding for the historic waterways.

New Mexico has more than 700 of the vital irrigation channels, and recent wildfires and other disasters have caused millions of dollars of damage to them far beyond what lawmakers have approved so far. Specifically, acequias will need $68 million in the coming decades to fix damage caused by disasters or harden against future ones, according to a recent rough estimate. To that end, the New Mexico Acequia Association is pushing House Bill 330, which would create a recurring infrastructure fund for acequias and land grants. You can read more here about what acequia leaders are seeking this session. Association Director Paula Garcia told Source New Mexico in a phone interview Tuesday that the extra funding is vital amid federal delays in funding acequia restoration and even freezes. Her association had a $200,000 “equity in conservation” grant from the National Resource Conservation Service it used to provide technical assistance to acequias in Lincoln and Rio Arriba counties, which were affected by fires and floods last year. The grant was frozen, Garcia said, probably due to some kind of “misunderstanding that it had to do with diversity.” It was a major source of funding for the small nonprofit, she said. In fact, “We used that funding to help everybody,” she said. “For under-served, rural areas.” Approximately 75 acequias sustained damage in the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire, and Garcia estimated that 10 of them, at most, had received the major construction they needed to repair from past damage or prepare for future floods. Around the time the acequia demonstration occurred Tuesday, lawmakers in the House Agriculture, Acequias and Water Resources Committee were hearing a bill allowing the funding of the Strategic Water Supply. Lawmakers narrowly approved the bill, which would approve up to $75 million to be spent as the state creates a market for the sale of treated brackish and produced water. Garcia said her association has not taken a position on the strategic water supply, but she did share some concerns that she’s brought to the attention of the bill’s sponsors. For one, she’s concerned that brackish water more than 2,500 feet below the surface isn’t subject to the same water rights application process as water closer to the surface. She is also seeking assurances that no produced water will be granted a discharge permit that would allow it to flow into rivers or farmers’ fields via acequias. Proponents have repeatedly said no such permits would be allowed. “It’s a very significant leap in the way water management is being handled in New Mexico, so it should be done very carefully,” she said. Bill watch The Senate Tax, Business and Transportation unanimously approved the Medical Psilocybin Act, which would create a program for New Mexicans to establish a program for medicinal use of psilocybin mushrooms. The House Consumer and Public Affairs Committee in the afternoon voted unanimously in favor of Rep. Marian Matthews’ House Bill 111, which would require first responders in emergencies to make a “reasonable effort” to find qualified service animals if they are missing. The committee also approved a proposal that would strengthen New Mexico’s protections for journalists from unfair subpoenas by state government officials.

Interview with Mariaelena Jaramillo

By Jessica Rath After talking to quite a number of individuals from Abiquiú and around for the Abiquiú News, one thing stands out for me: the strong sense of community most of these people have. They want to serve and help others, they put time and energy into supporting those around them, more often than not on a purely voluntary basis. Less concerned with their own dreams, they assist those near them to lead fulfilling lives.

Mariaelena Jaramillo is the perfect example. Besides being a mother and working a busy job, she’s involved with several groups which teach fun and useful skills to children and youth. Instructing traditional dances which honor Abiquiú’s forebears. A leader at the Rio Arriba County 4-H Youth Development Program. Coaching a group of cheerleaders at the elementary school. Mari, as her friends call her, is passionate about her culture’s beautiful traditions and about passing them on to the younger folk.

I have known Mari and her family for over 20 years, from my time as a volunteer at the Fire Department, when her father, Ben Jaramillo, was Captain. There was only one other non-Spanish speaking member, but I was always treated with warmth and kindness. Recently, I saw some photos of her and some 4-H kids at the Roundhouse, meeting with State Senator Leo Jaramillo. What a great experience for the youngsters! I wanted to find out what else Mari is up to these days, and she kindly took some time out of her full agenda.

Mari’s family has lived in Abiquiú for many generations. She’s a Genizera, as she tells me with a mix of pride and sadness. Her ancestors were descendants of Native American women and children who were captured by or sold into servitude to Spanish colonial families. They were converted to Catholicism, had to learn Spanish, and were forced to work as household servants or in the fields, not much different from slaves. During the second half of the 18th century, the Spanish offered land for settlement to Genizaros, in order to establish “buffer zones” against attacks by nomadic tribes.

The third of such Genizaro settlements in the New Mexico province was Santo Tomás de Abiquiú, established in 1754. In exchange for a perilous existence in the face of raids by Ute, Comanche, and Navajo, for example, the Genizaro were granted land where they could build their village. This was the only way for them to obtain their own property. “Our people were Native Americans, ARE Native Americans,” Mari told me. “It's just that we don't know exactly which tribe we belong to, because when the Spanish came in and colonized this area, they converted everybody to Catholicism.” She continued: “Being Genizaro is a tradition all of its own and a culture all of its own. Our kids should honor their culture, they should be able to represent it, to carry it on to the next generation. That's what I'm hoping to do: I put all these efforts into this, hoping that it's going to encourage somebody else to do the same for the next upcoming group of kids.” Here is a PBS documentary exploring the Genizaro Experience:

One way Mari continues the Genizaro culture involves teaching the traditional dances with their gorgeous costumes, stunning headdresses, and beautiful face paint.

Mari explained: “Originally, we did our dances during Santo Tomás, in November right after Thanksgiving. That's when we traditionally had them. That was the way of the Spanish incorporating the Native Americans and enticing them to come to Church. It was a way of conversion, and of inclusion.”

“Now we're doing it at different times of the year because we get asked out to dance, and I am very proud of the girls that I am dancing with right now. I'm honored to have them dancing, because they're out there, they're doing it. They're not embarrassed, they're proud of who they are.” When I look at the pictures Mari shared with me, I understand why she is so enthusiastic. They’re simply exquisite!

Mari wants to revive the Matachines Dances which haven't been performed in Abiquiú for over 80 years. The dances have roots in medieval Spain with Moorish influences as well as in Southamerican legends and weave together both Christian and Indigenous religious beliefs.

I learned from Mari that there are still some descendants of those original families. “Recently we had our first invite-meeting to see if any of these families would be interested in coming and representing their family, honoring their family,” she told me. “These dances are tied to religion. When the Spaniards were conquering the world, paganism was bad. Anybody who wasn’t worshiping God was bad. This was their way of making the people of these little pueblos come to church, because they let them do a performance, a dance.” I found an article about the Matachines performance at the Santuario de Chimayó, and it looks fascinating – I hope that we’ll be able to see a performance in Abiquiú! Mari pointed me to a video produced by the Smithsonian for their “Living Cultures” series, filmed in front of the Morada Del Alto.

Mari commented: “If you look around, you'll find us. We danced in front of the Morada Del Alto, up in the village. Delilah, Chavela, Dexter, Virgil, a few of the girls that I'm dancing with, like Audrey, – she still dances, and Juliette, she's still dancing. Angel danced, but now that she’s older she wants to drum, and she's good at it.” Take a look, you may recognize a lot of people!

Next, I wanted to learn about Mari’s involvement with the 4-H program, where she’s a leader at the Rio Arriba County 4-H. She had exciting news, actually: she will be taking a group of six 4-H kids to Washington, DC! If they’re able to collect enough funds, that is. 4-H is a nonprofit organization and they don’t have the money to finance projects such as this one. SO: if any of you Abiquiú News readers feel motivated to support Mari and her endeavor, please call the Rio Arriba County Extension Office at 505-685-4523 and ask for Lucinda, the new 4-H agent. Mari spoke highly of her:

“I'm giving her many high points and lots of credit. We haven't had a 4-H agent here in our county for almost five years now. We've had sit-in agents like Joy and Donald, and they have done great, they've kept our head above water with 4-H. But hopefully this lady will be able to take us a step further, and maybe she'll be able to unite 4-H again.”

Mari continued to explain. “In our county, 4-H used to be very united. We used to have clubs all over and we'd have 100 kids that would show up to events, just from our county of Rio Arriba. They would come from Dulce, from down in Espanola, up in Mesa Vista, up in Ojo Caliente, and all the way from Gallina. Everybody would come, it didn't matter from where, because we were united. Now it's not like that. The only thing people come to 4-H for now is for the County Fair, to show their animals, to sell their animals. That’s ONE purpose of 4-H but it goes way beyond that. 4-H is about the life lessons you'll be able to learn, the friendships you get to make, the relationships you get to make, the contacts you get to know.”

“We just had the privilege of going to the Round House”, Mari continued. “We had the honor of meeting our State Senator Leo Jaramillo, who grew up in Rio Arriba and graduated from Espanola Valley High School. You know, it's nice to see that people can come from this area, from our county, from these small, little places, and make a big name for themselves, become something. And it's wonderful that they're able to come back and bring something back to our community.”

What are some other skills that young people can learn from 4-H, I wanted to know. Mari answered excitedly: “The sky's the limit with 4-H! You tell me what you're interested in, and there's a project for you. We do Legos. We do horticulture, entomology, livestock, shooting sports, arts and crafts, sewing, cooking, baking, consumer decision making, and rocketry. I guarantee you there's a project for you to do. It's just a matter of people participating, being involved. COVID deprived us of that, especially the youth in our area. They don't know how to come together and be together, to drop the phone, leave the phone aside. They can't socialize any more. I hope things will improve, now that we have a 4-H agent again.” I hope so too; what a great way to find out what interests you as a young person.

As if teaching traditional dances and being a 4-H leader weren’t enough, Mari also is a cheerleading coach at the Abiquiú Elementary School.

I’m so impressed, listening to her: “I first started when Felisiana was in third or fourth grade, and then during her fifth and sixth grade year I think it was COVID why we stopped. I didn't do it for a couple of years. I started again when LilahRose (Mari’s second daughter, now nine years old) entered first grade. This will be my third year doing coaching with the Abiquiú Cheerleaders. Mr. Noble and Abiquiú Inn generously donated us money, and my girls were able to buy new uniforms. Because the old cheerleading uniforms were older than the kids, you know? So I asked Mr. Noble here at the Abiquiú Inn, and he kindly donated money for these young ladies, so we were able to dress our girls. We had 12 cheerleaders that year. This last year, I had eight, and this coming year, let's see what happens!”

“This last year my girls had the honor of going to the high school and performing with the high school squad during one of their homecoming games. That was pretty cool and the girls liked that, for sure.” Mari went on: “We need coaches. We need somebody who's willing to spend an hour of their day to help these kids. Because that's what normally happens: parents are there when their kids are there, but what happens the rest of the time? There has to be somebody who's willing to take that up. It's like that at church too. During Christmas, we did the Posadas, the kids did the whole thing on Christmas Eve, which was beautiful and wonderful to see.”

“But it takes time. It takes somebody to go and look for the costumes. I did it, and I don’t want credit, but it takes somebody's time and I just hope there's someone else somewhere down the line who's willing to carry that along. Especially when it comes to the traditions of our small communities.”

Mari made me think about what she said next: “I think a lot of us don't question that we’re Catholic, because we are. But when you stop and think about it, are we really, were we really supposed to have been? And maybe we weren't, because maybe our ancestors believed something else. They were forced to become Catholic, because sometimes it's easier to go with it than to fight it.” “It was easier to say, ‘Fine, I'll be a Spaniard. I'm Hispanic. Now I'm converted. I get to stay here, and you're going to give me a little piece of property to live on, okay? I'm Spanish, and I won't use my Native language any longer, I'll speak Spanish.’ Then all of a sudden, they told us, now you can't speak Spanish, now you must speak English. Now you're white.. It's sad how it happens. But a lot of the time we don't realize it. We just take it for granted that we are white, that we are Hispanic, that we are this or that, and in reality, we're not.” Well, I think Mari deserves a lot of credit for everything she does for the community, and maybe she’ll inspire somebody else to follow her example and keep the customs and traditions alive. Thank you, Mari, I’m so impressed by everything you do, and I wish you and all the kids you interact with a great deal of success! By Zach Hively Images Courtesy of Zach Hively Here's to Tom Robbins, Ms. Galvin, and the books that shape us. I want to tell you about the first two times I was murdered. But first, you need to know about Paige Galvin. Ms. Galvin taught me in sophomore year of high school. I have no idea what she taught me, as far as my transcript was concerned—it wasn’t any of the core subjects. It also wasn’t any of the elective subjects. She taught a practical class, though; a practical class on getting away with murder. Take, for instance, how she got the school administration to approve a class that had some undefinable yet sanctionable course title, something like “Communication Skills” or “Proficiency Seminar” or “Algebra II.” We had, I recall, six or eight students enrolled in that class. That’s the official tally. We actually had ten to fifteen students in the room during any given period. Ms. Galvin evangelized that it was better to ditch classes in her classroom than to ditch them, I don’t know, in a ditch somewhere. Ditches are deadly—but the couches in Ms. Galvin’s room were comfy. Besides, why should we be allowed eleven absences per class each semester if not to use them when we pleased? The syllabus for “Enhanced Dialogue,” or whatever it was called, existed merely as an alibi to cover all our butts. We never so much as referenced it. One class, for instance, we had a lively group discussion about whether my classmate was dumb, or whether she was really dumb, for getting her nipples pierced. We could always bring in CDs but only if we could share insights about the music. A not-insignificant part of the class was troubleshooting how to deal with intolerable teachers in more traditional subject areas. I remember only one rule, strictly enforced: never use the R-word. The wall had an actual hole, ten inches square, between our classroom and the next-door class for R-word students. It occurs to me now that Ms. Galvin quite possibly punched that hole herself (or asked a geography-ditching student to do it) in order to teach us with first-hand embarrassment. Tactical empathy: some murders are not worth getting away with. Others, however, are. We’d been reading Very Good Books in English class that year. They also happened to be Very Dull Books for 15- and 16-Year-Olds. Like, I mean, Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar is fine and all. Reading it made sure I get all the “ides” jokes every mid-March. But the play contains way fewer genitalia references than the bard’s best work. This—the existence of good but unengaging books—might have been the flint that sparked the fire that got away with murder. One day, Ms. Galvin sent me on a quest to the school library in the middle of the period. Here I was, ditching the class I was ditching class in, with an illicit bathroom pass in hand, strolling through the empty, echoing halls. The book I had to find was a smaller paperback than I expected. I’d been reading bulkier books since elementary school—and what a strange title, Slaughterhouse-Five. A hyphen has never enticed me so, before or since. “Read it.” That’s all Ms. Galvin said. So I did—and it was better than getting away with murder. Better than the kissing I had yet to manage. Better than the drugs that other people, both cooler and less cool than me, were reportedly doing. Better than my classmate asking us if we wanted to see her nipple rings and ditching Spanish put together. Were people allowed to feel colors the way this book made me? It didn’t matter what was allowed. I didn’t have to write any essays on the symbolism of the snowfall. I just got to read it, and to read it again, and it got to murder me, the me that existed before. Ms. Galvin did it again when I graduated. She gave me another book—all mine, no library due date, signed by the author and everything. Tom Robbins, the old rascal, died this week at the age of ninety-two, which is why I’m back to thinking about Ms. Galvin. Another Roadside Attraction didn’t quite turn me inside out in four-color—that happened a couple years later when my dad gave me Even Cowgirls Get the Blues for my twentieth birthday, when I survived my second murder. RIP to yet another long-gone version of myself. Yet this book is the only memorable one from my TBR stack that summer between high school and college. And so it is the book I link, for good, with the worst financial decision I have ever made in all my years so far: to circle my life around the soothing and unassuming tactile experience of getting away with murder. AKA, books. Every book is magical: ink on paper makes you imagine things, conveys knowledge, evokes emotions. Every book has the potential to destroy who you thought you were and show you who you could be. Forget shaping me as a writer; the works of Tom Robbins shape who I am as a human. (Ha ha ho ho and hee hee.)

I might be the worst-case result of such exposure. Most young people who dabble with dangerous texts don’t turn around to become at various points booksellers, publishers, and—to their families’ continued dismay—attempted professional writers. But that’s not to say you, too, shouldn’t corrupt the youth. Doing so is not yet entirely illegal—and even if it gets there, it will only encourage the Ms. Galvins of the world. Even though she taught me so much about thinking, I still can’t think of a better misuse of adult responsibility and trustworthiness than to give a kid a book outside in the syllabus. Let them think they’re getting away with murder. Because they are. ________________________________________ I’d love to know what books shaped your life, rearranged you from the inside out, changed who you are as a person. What book would you share with a young reader to change their existence? An Unforgettable Evening of Music & Community Featuring World-Renowned Russian Pianist Katya Grineva2/10/2025 Fuller Lodge,

Los Alamos, NM 4:00 PM, March 1, 2025 Espanola, NM – Prepare for an inspiring night of music and community! Moving Arts, in partnership with the Los Alamos Arts Council, invites you to a magical celebration featuring the breathtaking talent of world-renowned Russian pianist Katya Grineva. Fresh from her 22nd season at Carnegie Hall, Katya’s spellbinding performance will leave you in awe. Enjoy delicious appetizers lovingly crafted by the Moving Arts Health Meals Program. Sip on refreshing mocktails. Get an exclusive first look at an upcoming documentary that showcases the transformative work of Moving Arts. Come for the music. Stay for the vision. Learn how Moving Arts is shaping a brighter future for our children and families with a Community Hub of Family-Centered Services. This free event is your chance to be part of something truly special. Mark your calendar and tell your friends about this community celebration of music. RSVP for this amazing evening at movingartsespanola.org/events. During her stay in New Mexico Katya, will also perform for local youth in Los Alamos to inspire a love of music and the arts. Giving youth the opportunity to engage in the arts is paramount to the nonprofit organization she created in New York. Moving Arts is a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing access to creative and experiential learning, offering a safe space where children and youth can explore their interests, expand their knowledge, and develop into confident contributors to their communities. For more information, please contact: 📧 Email: [email protected] By Nicole Maxwell

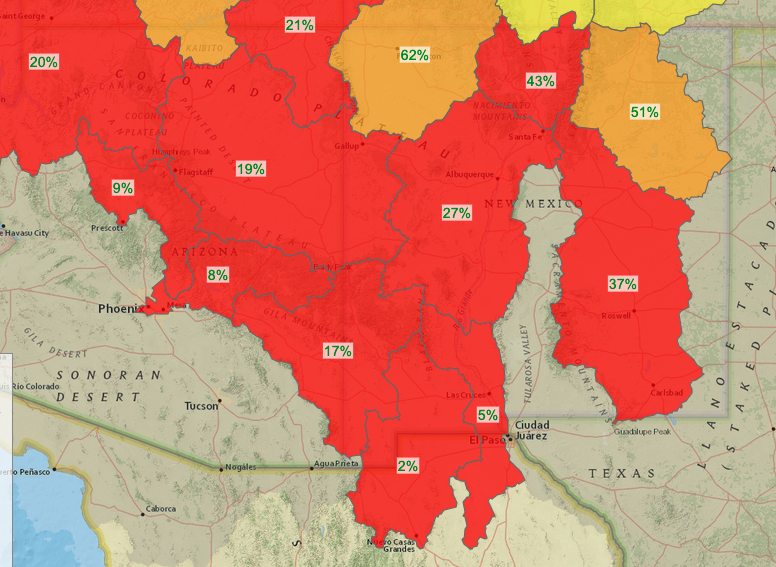

NM Political Report The measure would tie public funding to policies prohibiting removal of books A bill aimed at protecting public libraries from politically charged book ban attempts is making its way through the Roundhouse. HB 27, the Librarian Protection Act, sponsored by Rep. Kathleen Cates, D-Rio Rancho, seeks to prohibit public libraries from getting state funding unless they adopt a policy prohibiting the removal of books or other materials based on partisan or doctrinal disapproval. “I bring this bill to you today because I have concern about our public librarians throughout our state, and I believe that this is a bill that will help protect them,” Cates said during a committee hearing. “As you know, librarians have spent their careers in education and being able to serve their community, and they’re all about process, not about politics, and I want to be able to let them stay in that process-oriented manner of decision.” The bill also does not allow a public library’s funding to be reduced for complying with the bill. “The bill clarifies that it is not intended to curtail the right of individuals to challenge library materials. ‘Ban’ means the removal of library materials. ‘Challenge’ means the attempt to remove said materials,” the bill’s Fiscal Impact Report states. From 2024: Legislators seek to stop libraries from banning books “The Public Education Department notes that if the bill is not passed, public libraries in New Mexico may be subject to increasing numbers of challenges to books and other library materials, based upon partisan, political, or religious views, hampering their general mission of provision of information, books, and other resources to the public,” according to the report. The process for challenging books and other materials would remain intact, however, blanket bans based on political or other ideological reasons. The bill passed the House Consumer and Public Affairs Committee 4-to-2 with Reps. Stefani Lord, R-Sandia Park, and John Block, R-Alamogordo, voting against the bill. Lord said she was against the bill because it does not directly prohibit children from accessing materials shelved in the adult section due to adult content potentially not being appropriate for children. About a year ago, Estancia Public Library Director Angela Creamer set up Freedom to Read, a policy that includes how the library would handle someone coming in and asking for materials to be removed. “I think a lot of politicians maybe forget that librarians are men and women that are also parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, and we care about our community just as much as anybody else,” Creamer said. “Personally, I don’t think the government should be raising our children. I think parents and caregivers, guardians and grandparents and relatives raise the children. So I think it goes back to trust.” The Rio Rancho City Council in 2023 passed legislation protecting public libraries and librarians from repeated, but ultimately unsuccessful book banning attempts. While historic snow fell across swamps and beaches in the Eastern United States in January, New Mexico’s snowpacks are looking high and dry at the beginning of February.

New Mexico had its hottest autumn ever, with October through December marking the warmest temperatures on average since 1895, said Tony Bergantino, the director at the Wyoming State Climate office, which collects water and temperature data for the Equality State. Bergantino led the Intermountain West Drought and climate briefing on Tuesday hosted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and its federal drought arm. He noted that in addition to the hotter temperatures, New Mexico snowpacks are well below their median size, which threatens rivers that rely on snow water. Temperatures range anywhere from 11 to 22 degrees above average for this time of year, from mid-60s to high 70s around the state. Conditions are hot and dry enough that the National Weather Service office in Albuquerque issued a red flag warning for Wednesday due to the potential fire danger over about a quarter of the state, covering much of the northeastern third. It’s the second this year, with the first issued on Jan. 4. While there will be colder temperatures moving back in for eastern NM this weekend, snow or rain forecasts look slim, said Randall Hergert, a forecaster with the NWS in Albuquerque. “There are no good signals for a good, beneficial storm to put us on the right track in these closing months of winter,” Hergert said. Atmospheric patterns and currents in the Pacific Ocean, which dictate weather patterns, are currently in a La Niña cycle, meaning that New Mexico is forecast to have hotter and drier weather for at least the next three months. Warming from human caused-climate change exacerbates those natural trends, which is worsening drought, intensifying storms and wildfires in New Mexico. The departure of Agapita “Pita” Judy Lopez, Georgia O’Keeffe’s former companion and mainstay of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation and Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, left big shoes to fill at O’Keeffe’s Home & Studio in Abiquiú.

With two decades of experience in art and curatorial work and seven years at the O’Keeffe, Giustina Renzoni was recently appointed Director of Historic Properties and is ready to take the next steps in projects and operations in Abiquiú at the Welcome Center, Home & Studio, and O’Keeffe’s Home at Ghost Ranch. Let’s get to know Giustina Renzoni. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum: First congratulations on your new role. But before we talk more about you, we’d be remiss if we didn’t first talk about Pita. You worked with her probably closer than anyone else in recent years, what was that like? Giustina Renzoni: In the realm of historic houses and properties, it’s exceedingly rare to work with someone like Pita and her brothers, Maggie, Mino, and Steve. Not only is she extremely generous in sharing her knowledge and memories, but her leadership ensured that the direction we are moving in has always stayed true to O’Keeffe’s intentions. She and the Lopez family really embraced me and I’m so thankful for her friendship. I will never be Pita but with her mentorship, inspiration, and all that she taught me, I’m confident and excited for what’s to come. GOKM: Can you tell us a little bit about your career and how it led you to New Mexico? GR: I’ve been working in museums since I was 19, when I started as a gallery attendant. After spending time as a research curatorial assistant, working for an auction house, managing galleries, and even on a preparator team, I explored many aspects of working in the arts and knew I wanted a career in museums. Eventually, I found my way from my hometown of Boston to Denver, where I worked for the Denver Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. I was living in Colorado and traveling to New Mexico for years, camping and exploring. During those trips, as clichéd as it sounds, I really fell in love with the landscape and the history of Northern New Mexico. GOKM: What drew you to working for the Museum? GR: I grew up in New England, the daughter of an architect, and just down the street from a historic home once owned by a Revolutionary War general. Needless to say, I visited a lot of historic houses throughout my childhood. But aside from visiting them, I didn’t know much about maintaining them. When the opportunity to work for the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum came up, I was thrilled. First, there aren’t many museums dedicated to a woman, and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum is exceptional for its collections and archives—artwork, correspondence, photographs, oral histories, books, textiles—it’s incredible. The Historic Properties perfectly combine my interests in Spanish colonial visual culture, New Mexican history, and modern design, so that was a huge draw. The house itself is so dynamic—it held two centuries of history even before O’Keeffe stepped onto the property. When she purchased and renovated it, she didn’t try to hide those layers. Instead, she embraced them, putting her own spin on the space. It gives such valuable insight into O’Keeffe as a person, not just an artist. GOKM: You’ve overseen exhibitions and overseeing tours in Abiquiú for seven years now. What short- and long-term goals for the Home & Studio do you have in your new position? There is a lot more in the house and its history that we haven’t been able to tap into yet. This year, we are offering a new tour for families and children that sees the Home & Studio through the eyes of an explorer. It will have Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math (STEAM) principles that connect with school curriculums. I’m hopeful this tour can help us grow our field trip program and connect with local youth. In the long term, I want to continue to find ways to offer new experiences and increase access to the homes in Abiquiú and at Ghost Ranch, while prioritizing the stewardship and preservation of those sites. What that looks like right now I’m not sure, but we have a really great team that continually finds ways to keep the space alive and dynamic. GOKM: You curate the objects seen on the Home & Studio tours, including O’Keeffe’s clothes. What’s your favorite piece of clothing in the Collection? GR: An Emilio Pucci dress from Lord & Taylor. While it’s in the black and white palette O’Keeffe preferred, this is not the sort of dress she is typically envisioned wearing. It’s predominately white instead of black, with subtle details like an asymmetric collar, contrasting cuffs, and the color blocking. There is a combination of details and simplicity that is understated and powerful at the same time. GOKM: Do you have a favorite piece of furniture in the Collection? GR: Curating Artful Living: O’Keeffe and Modern Design, a recent exhibition of O’Keeffe’s personal effects at the Welcome Center, gave me a deeper knowledge of the decorative arts collection and why O’Keeffe collected so much furniture. My favorite piece is a beautiful upright leather chair by Mogens Kold, a Danish company. The frame is made of rosewood, which is now considered endangered due to over-harvesting, so you rarely see it in furniture now. It’s an exceptionally minimalist piece, but the slight curves give the traditional silhouette an organic shape. You can really see the detail of the wood grain, which gives a beautiful contrast to the rich, black leather. It’s a striking example of mid-century Scandinavian design and craftsmanship. --Artful Living: O’Keeffe and Modern Design is on view through 2025 at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Welcome Center in Abiquiú. Interested in visiting Georgia O’Keeffe’s historic Home & Studio? Tickets are now available for Standard and Extended Tours beginning in March and for brand new offerings kicking off in June! Visit gokm.org for ticket information. Last Monday, January 27th, we experienced a sharp decline in tech stocks, particularly Nvidia, which suffered the largest single-day market cap loss in the history of the stock market. This dragged down other stocks too – the NASDAQ was down over 3% in 1 day! This sort of market decline challenges us as investors to reflect on our emotional reaction to the drop. A reaction of fear or panic probably indicates that you have an overexposed and too risky portfolio.

I’ve been talking about reducing risk in our portfolios for months. Bull markets tend to breed overconfidence, which, if that happens, can lead to poor investment decisions. Proper portfolio construction is essential for long-term stability and peace of mind, especially in volatile markets, which is where we are now. Peace of mind on your investments is very important because without it even worse investment decisions can follow. If you feel your exposure to equities (stocks) is too high, it might be time to consider working in some protected investments to your portfolio. This could lock in gains you’ve experienced and protect you from downturns that I think are inevitable going forward. Equity Markets have gone up over time. That’s a fact. But they also can be quite volatile at times, leading to big losses. Those losses have proven to be temporary, and that’s great in the long run. But it can take years to get back even, and not all of us have years to recoup losses. That’s why having guaranteed investments as part of your portfolio make sense at all times but especially now. If you’d like to get another opinion on your investments, feel free to contact me. There is no obligation or cost to simply get an opinion. I’d be happy to do it for you. Peter J Nagle [email protected] 505-423-5378 Let’s just get this out of the way: I dance Argentine tango. By Zach Hively Despite what some family members have asked out loud, Argentine tango is not a weird sex thing. It is intensely intimate at times, yes, and sometimes it is over way too soon. I also know what a lot of married women’s shampoo smells like. But, in my years of experience, every one of my fellow dancers has been—and has remained, for the duration of the dance—fully clothed. Sometimes, that is the best thing I can say for my fellow dancers’ wardrobe choices: that they are, in fact, wearing things. Also! I can confidently say, just by looking at them and with no other context, that these dancers have dressed themselves. Which dancers? Well, one of the things I love about tango today is the way the community is prying apart binary gender roles. Followers are not always women, and leaders are not always not-women. Space for queer tango is growing, as is space for trans people in tango, and space for cis-gendered people to role-switch. This culture of growing acceptance makes me balk at criticizing any particular demographic for its underwhelming tango fashion but it’s men. It’s always men. Everyone Else in tango recognizes that how they present themselves reflects their care and dedication to the dance, and that doing so with even marginal intent improves their chances of getting to dance. At the very least, Everyone Else reduces the likelihood of embarrassing themselves with the equivalent of showing up to senior prom in a baggy paper sack. Men, I am increasingly convinced, cannot be embarrassed, even though they should be. #notallmen, of course. Like, not me. I can be embarrassed. That’s why I have such a snobbish attitude about dressing well for this most complex, subtle, rebellious yet also gentrified dance. My snobbishness stems from my discovery that I can pay someone, for less than the cost of a new shirt at Ross, to clean and press my existing ones. Are crisp shirts the main reason I get dances? No—they are the only reason. Pressed shirts add a certain, how do you say, sense that you don’t always live out of a laundry basket. Everyone Else finds this a desirable quality, or at least a baseline requirement. (Also, I respect when a woman declines to dance with me and I do not speak poorly of her. Not even on the internet. But this reason is probably secondary to my shirts.) Thus, I swear that men, used to getting a very great deal of what they want with very little resistance, could actually get more dances and jobs and loan forgiveness and such in all areas of life if only they would put any effort at all into their wardrobe. So, here is my expert guide for How to Dress Yourself More Better for Tango, My Man—and Also for Life, divvied into four tiers according to your level of entry: Basic Tier • Wear clothes that fit. • Not clothes that used to fit. • And not clothes you want to fit. • And definitely not clothes that fit in the sense that a sandwich fits inside a Toyota Camry. • Clothes that fit function well with the shape of your body as it is. • Bonus points if you figure out the right orientation for stripes to make you look better than you actually do, without the strain of sucking in your gut. • Could you wear those clothes golfing? Then don’t wear them to dance. • Don’t wear them anywhere at all, really. • Not even for golfing. • Does the shirt tuck in? Then tuck it in. • Unless it’s a shirt not meant to be tucked. • Or a style that doesn’t demand it. • But when in doubt, tuck it. • And then wear a belt. • A real belt, with a buckle. • Also with loops. • Then, adjust the belt to fit. A droopy belt makes us imagine what else droops. • We all love that you did that 5k fun run or saw the Steve Miller Band in concert. • But don’t wear the tee. • Unless you’re attending a function with the word “picnic” in the name and the event will be held in daylight from start to end, best to avoid screen-prints altogether. Cheat Code: You don’t need a big budget to own yourself. Find your style at the thrift store. You never have to worry about your clothes going out of style if you’re the one bringing them back into style. Manning-Up Tier • You might think your stonewashed jeans are stylish. • They are not. • Unless bolo ties are standard issue where you’re going, ditch the denim. • But not for shorts. Dear Tim Gunn, not for shorts. • Slacks are not that hard, my man. And they’re comfy. • Especially if you buy them four inches too large in the waist and have someone take in the waist to the appropriate size. • Then your legs have room to actually move. • Yeah yeah, skinny pants are sometimes in. Don’t care. If you can manage skinny pants in public, you don’t need this expert guide. • Shirt come untucked? Tuck it back in. Gentleman’s Tier

• Find your colors. • And yes, black and white are colors. • Consider your ability to move. • Will you be plucking clothes out of your various crevasses whenever you stand up? • Can people picture you naked without using their imagination? • Do you want them to? • (No. You don’t.) • Long sleeves rolled up look classier than short sleeves. • I am the author of this guide, and my opinion is gospel. • But you do you, babe. • That said: If you wear short sleeves and look like somebody’s—anybody’s—dad on vacation or a stock photo for casual Friday, please return to the Basic Tier. Ooh La La Tier • Grooming is not just for horses. • A little care for your hair, everywhere it can be seen, will stand you a lot apart from your fellow man. • Yes, even that one lone hair. • Especially that one. • Accessorize. • Damn right, accessorize. Rings or cuffs or watches or cute socks. • Anything, really, to infuse some personality for all those people who can’t see, or don’t care to see, the work you put into your car or other male personality extender. • I wear ascots, for instance. • So choose something else. Basically, my man, my men: We all need to show up better in the world, in tango and out. Sure, we need to show up as trustworthy friends, and protectors, and partners, and leaders, and firemen and astronauts and civil servants and stuff too. But dressing the part is both essential, and easier. It’s literally the least we can do—putting ourselves together to give the impression that we care. If enough of us do this, the next great differentiator can be actually caring. But my hopes for us aren’t that high. We can’t even keep our shirts tucked in. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed